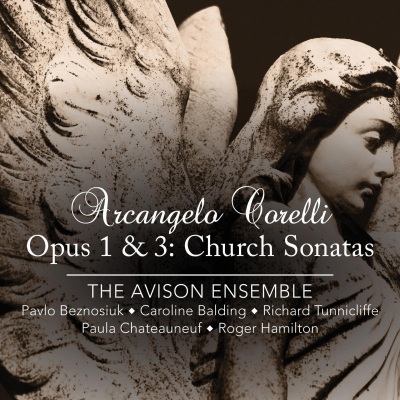

Corelli: Church Sonatas, Opus 1 & 3

'Opus 1 & 3: Church Sonatas' is the final recording in The Avison Ensemble's welcome undertaking to record Corelli's complete chamber music in celebration of the 300th anniversary of the composer's death. 'I have enjoyed every one of the discs in this series from Linn Records so far, and this last set more than lives up to expectations. These are, in sum, sincere and poised accounts, a fitting tribute to the 'chaste and faultless' character of the composer and his music.' BBC Music Magazine 'The illustrious five players of the Avison Ensemble offer shapely readings, phrasing beautifully and making the most of every nuance.' The Sunday Times A fittingly satisfying finale to the series, Corelli's church sonatas are exquisite, highly refined compositions representing a high point of Italian Baroque instrumental music. Corelli's contribution to the history of violin performance was immense. All six of his published collections of instrumental music demonstrate his exceptional skill as a violinist and composer. The series has been greeted with wide critical acclaim: Opus 2 & 4 was named ‘Recording of the Month' by Musicweb International which also named Opus 6 a 2012 ‘Recording of the Year', whilst Opus 5 was awarded stars by BBC Music Magazine who praised Beznosiuk's 'intuitively musical performances.' Arcangelo Corelli 1681 was a largely uneventful year in the history of the Western world; the same can also be said of musical history. That year saw the births of the future eminent musicians Georg Philipp Telemann and Johann Mattheson but little else of consequence occurred. However, there was one other major occurrence and that was the issue of a set of twelve trio sonatas, printed by the Roman publisher Giovanni Angelo Mutij. At first glance the publication of a set of sonatas should hardly have been a noteworthy event; the Mantuan composer Salomone Rossi had published similar works as early as 1607, and numerous other comparable sets had appeared over the subsequent seventy-four years. What placed the 1681 set above all others was that it became an important landmark in the development of Western classical music. Published as the Op. 1, this set of sonatas originated from the quill of the Italian musician Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713), a man who was then more highly regarded for his skill as a violinist than his compositional ability. Nevertheless, it was through this set and his subsequent five opera that Corelli established himself as one of the most celebrated and influential composers in Europe, and secured a prominent place in the roll call of the greatest musicians of all time. By the time of the Op. 1's publication in 1681, Corelli had been settled in Rome for a number of years. He had arrived in the Italian capital by 1675, before which he had spent time in study at both Lugo and Bologna. In Rome, Corelli cultivated his career as a violinist through his participation in various church orchestras, ultimately becoming one of the foremost violinists in that city. As with other musicians in Rome at that time, Corelli sought the support of a wealthy patron and in 1677 entered into the service of Christina, the former Queen of Sweden, who was then in the last of her four sojourns in that city. Queen Christina, who was well-known for her eccentric lifestyle and masculine mannerisms, abdicated in 1654 at the age of twenty-seven and soon after converted to Catholicism. Pope Alexander VII, who viewed her conversion as a victory, welcomed her into Rome in December 1655 and established her there in a manner that more befitted a reigning monarch. However, her behaviour and refusal to conform to the expected rules of conduct caused a strain in her relationship with the papacy. Queen Christina was an avid supporter of the arts, particularly music, and was an accomplished musician herself. In 1674 she founded the Accademia Reale, a sanctuary for the cultural elite of her day, and cultivated a taste for French ballet and Italian music. By 1679, Corelli had begun to satisfy her musical desires by composing sonatas for the Academy held on the upper floor of her residence, the Palazzo Riario. Given the support that Queen Christina had shown Corelli, it is not a surprise that he chose to dedicate his first published work to her. Corelli was, however, wary of the criticism which might have befallen his Op. 1 Sonatas and requested that she protect ‘the first-fruits of my study'. Whatever fears Corelli had were soon quashed as, over the coming decades, his ‘first-fruits' were reissued by the entrepreneurial music publishers in Bologna, Venice, Modena, Antwerp, Amsterdam and London. They remained in print throughout the eighteenth century, a feat unrivalled by any earlier collection. Corelli's Op. 1 Sonatas, like those in the Op. 3 set, have been described as sonata da chiesa (church sonatas), despite the fact that Corelli did not use this term himself. Corelli referred to them as Sonate a trè, while Peter Allsop (1999) described them as ‘free' sonatas. Despite the implications of the da chiesa label, they were not conceived for use in church although, as Mattheson observed, they could be used to accompany worship. Corelli followed their success with another set of trio sonatas, the Op. 2 of 1685; they are of the da camera (chamber) type. For his 1689 Op. 3 Sonatas, Corelli returned to the da chiesa design. He dedicated this set to Francesco II d'Este of Modena, a wealthy patron of music and a capable musician. During Francesco's tenure as Duke of Modena, the city's cultural life had experienced a renaissance. He more than doubled the number of musicians at court, re-established the University of Modena, and vastly enlarged the great library, the Biblioteca Estense. Corelli's dedication led to speculation that he had spent time working at this vibrant musical centre, but there is no evidence to support such a visit. Francesco's first encounter with Corelli is believed to have been in 1686, when he had heard the virtuosic violinist play at the home of Benedetto Pamphili. Francesco subsequently made a move to secure Corelli's services for the Modenese court but Corelli, who was then well established in Rome, declined his offer. Unwilling to accept Corelli's rebuff, the Duke made several further unsuccessful attempts to lure Corelli to Modena. Notwithstanding Corelli's rejections, Francesco was grateful for the dedication and rewarded the composer through the gift of a hundred ounces of silver and a splendid silver casket. Corelli scored both the Op. 1 and 3 for three melodic stringed instruments and continuo, a favoured Roman arrangement. The two upper parts were intended for violins, and the bass part was originally written for violone or archlute. Exactly what Corelli meant by ‘violone' is unclear, given that there were at least three different sizes of bass violin in use at the time. The term did not refer to the violoncello, which was a distinctly different instrument. There was also a predilection for plucked stringed instruments in Rome, such as the lute, a trend that lasted well into Corelli's lifetime. Archlutes were regularly employed to fulfil a wide range of musical roles. They could be used as solo instruments, or to provide the bass and continuo parts to cantatas, operas, oratorios and various instrumental genres. Nevertheless, as the trios began to circulate Europe, it became commonplace for a cello to play the bass line; some early editions, including those by the London publishers John Walsh and John Johnson, specifically call for that instrument. Corelli had originally written the continuo part for an organ, although this again in no way implies that these sonatas were intended for church use. At the time, organs were commonly used as chamber instruments and were the preferred choice to provide the continuo. Queen Christina's music room possessed two organs, as well as two harpsichords and two spinets. If an organ was unavailable, another keyboard instrument, such as the harpsichord, would make a suitable alternative. In composing these sonatas Corelli drew upon two principal areas of musical activity, that of Bologna and Rome. Evidence of the Bolognese influence can be found within the music itself; some of the most important influences on Corelli were Maurizio Cazzati, Giovanni Battista Bassani and Giovanni Battista Vitali. Although Corelli never acknowledged the Bolognese influence outside his music, his adoption of the moniker ‘Il Bolognese' has always been considered sufficient proof of this debt. However, a clear reference to the Bolognese school can be found in the second movement of Sonata Op. 1 No. 1, where Corelli pays a compliment to Cazzati through the reuse of material from his sonata La Casala, Op. 35 (1665). In Rome, Corelli immersed himself in the study of music by Roman masters including Alessandro Stradella, Lelio Colista, Carlo Mannelli and Carlo Ambrogio Lonati. He also studied composition with one of the singers of the papal chapel, Matteo Simonelli, who had, despite his limited number of compositions, been dubbed the ‘Palestrina of the seventeenth century'. Most of Corelli's da chiesa sonatas use a four-movement slow-fast-slow-fast plan, a layout with whose establishment Corelli has been credited. In the Op. 1, only the Sonata No. 4, with its three fast movements, deviates significantly from this plan. Of the other Sonatas, the seventh lacks an opening slow movement, while in Sonatas Nos. 6 and 12 Corelli places a ‘Largo' as the second movement; he also adds an opening ‘Allegro' to Sonata No. 9. Even though the four-movement SFSF form became commonplace in the eighteenth century, it was unusual in 1681. However, despite its association with Corelli, he was not the first to employ this pattern; it had already been used, albeit rarely, by composers such as Giovanni Battista Mazzaferrata and Petronio Franceschini. Within the four-movement plan Corelli tended to use a distinct pattern of movements, a model that was also widely imitated. Nearly all of the first movements are derived from the Bolognese School, particularly their slow duple-metre movements, while those in second position also tend to use a duple-metre and take the form of fugues. Many of the slow third movements are in triple time, while those in last place, which have a much lighter tone to the more serious second movements, are largely in simple or compound triple-metre and feature a regular phrase structure. A typical example is Sonata No. 11, which begins with a sombre ‘Grave', followed by an impressive fugal ‘Allegro' that features a chromatically descending theme. The connecting ‘Adagio', whose theme is linked with that of the ‘Grave', leads into an arresting ‘Allegro' finale. Thematic links within individual sonatas are generally slight, but a striking example can be found in Sonata No. 4 where the themes in the first three movements are formed out of a descending scale; this idea then returns in the finale as a conclusion to the Sonata. Just like Op. 1, the Op. 3 set was a huge success. Immediately after its Roman publication in 1689 it was reissued in Bologna and by 1691 it had also appeared in Modena, Venice and Antwerp. Bach was familiar with the Op. 3 set and borrowed the theme from the second movement of Sonata No. 4 for his Fugue in B minor, BWV. 579. This later set reinforces what Corelli had already established in the Op. 1. In the Op. 3, eleven sonatas have four movements and nine of these are the SFSF pattern. Thematic links continue to be slight, but similarities can be seen between the themes in some sonatas, for example the first two movements of Sonata No. 2. Many of the finales in the Op. 3 take the form of fugues. Regarding Corelli's two da chiesa sets, the English music historian Sir John Hawkins writing in 1776 thought highly of the Op. 3, but viewed the Op. 1 as ‘an essay towards that perfection to which he afterwards arrived; there is but little art and less adventure in it'. He went on to say that the Op. 3 is: The most elaborate of the four [sets of trios], as abounding in fugues. The first, the fourth, the sixth, and the ninth Sonata of this opera are the most distinguished; the latter has drawn tears from many an eye; but the whole is so excellent, that, exclusive of mere fancy, there is scarce any motive for preference. Like all of Corelli's other works, his church sonatas were widely imitated. Some sets of sonatas, such as those by Telemann and British composer William Topham, went so far as to record Corelli's influence on their title-pages; another British composer, John Ravenscroft, wrote a set of sonatas so similar to Corelli's own that the Amsterdam publisher, Michel Le Cène, attempted to pass it off as Corelli's Op. 7. Charles Avison held Corelli in particularly high esteem, and described him as ‘chaste and faultless' in his 1752 treatise, An Essay on Musical Expression. Predictably, Avison's first published work, his Op. 1 set of trio sonatas, has a marked deference to Corelli. Avison's teacher and a former pupil of Corelli, Francesco Geminiani, published concerti grossi arrangements of Corelli's Op. 1 No. 9 and five sonatas from the Op. 3 in 1735. Corelli achieved the status of a cult figurehead in England where his music was widely circulated and frequently performed. Hawkins recorded that for many years Corelli's trios were performed ‘before the play at both theatres in London', while Roger North said in circa 1710: ‘It [is] wonderfull to observe what a skratching of Correlli there is every where'. A remarkable indicator of how commonplace Corelli's music had become is recorded in a letter written by the Dean of Durham Cathedral, Spencer Cowper. In 1752 Cowper reported that a request for some Corelli at a local concert, which involved Avison, elicited the exaggerated claim that ‘there was not one part of Corelli that the children in the streets cou'd not whistle from beginning to end'. Numerous eighteenth-century writers praised Corelli's musical works and held them up as models of perfection. North thought that Corelli's music ‘ever will be valued against gold', while the French music theorist, Sébastien de Brossard, in his discussion of sonata da chiesa form, advised: ‘for models see the works of Corelli'. Charles Burney observed in 1789 that: Scarce a co[n]temporary musical writer, historian, or poet, neglected to celebrate his [Corelli's] genius and talents; and his productions have contributed longer to charm the lovers of Music by the mere powers of the bow, without the assistance of the human voice, than those of any composer yet existed. Corelli's trio sonatas are in every aspect a high point of Italian Baroque instrumental music. Even though what Corelli achieved in these works could hardly be defined as new, he was able to synthesise pre-established forms and ideas to create works that raised the musical bar to a new height. As such, Corelli's trios stand head and shoulders above the best examples by his Italian contemporaries. As time progressed, Corelli's compositions evolved from innovative, frequently imitated models to well-respected, timeless classics. Hawkins, almost ninety-five years after the publication of the Op. 1 set, wrote that: ...There is in every nation a style both in speaking and writing, which never becomes obsolete; a certain mode of phraseology, so consonant and congenial to the analogy and principles of its respective language, as to remain settled and unaltered. This...may be said of music; and accordingly it may be observed of the compositions of Corelli....Men remembered, and would refer to passages in it as to a classic author; and...do not hesitate to pronounce...that, of fine harmony and elegant modulation, they are the most perfect exemplars. Even today, over 200 years after Hawkins' comments and 300 years since the death of the great composer himself, these words still ring true. Corelli's music is exquisite, highly refined, and as close to perfection as any composition has ever come; it is and will remain, as both Avison and North observed, immortal. © Simon D. I. Fleming, 2014 Recording Information: Recorded at St George's Church, Chesterton, Cambridge, UK, 7-8 November 2011, 12-16 December 2011 and 11-17 January 2012 Produced and recorded by Philip Hobbs Assistant engineering by Robert Cammidge Post-production by Julia Thomas Design by gmtoucari.com