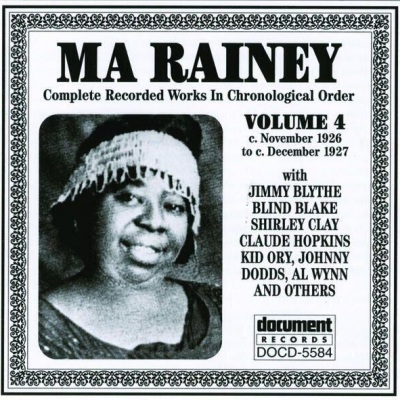

Ma Rainey Vol. 4 (1926-1927)

This is the fourth of five volumes dedicated to the complete recorded works of Gertrude Ma Rainey, released during the 1990s by Austria's Document label. Mapping her recording activities from November 1926 to December 1927 with 22 single take titles, it opens with "Morning Hour Blues," a straightforward number rendered somewhat hypnotic by the combination of Jimmy Blythe's piano, Blind Blake's guitar, and the delicately handled xylophone of Jimmy Bertrand. Ma Rainey's accompanists on this disc also include cornetist B.T. Wingfield, trumpeter Shirley Clay, trombonists Kid Ory and Albert Wynn, clarinetists Johnny Dodds and Artie Starks, violinist Leroy Pickett, and pianist Claude Hopkins, destined to lead his own big band in Harlem during the 1930s. Like every volume in the series, this is a potent storehouse of undiluted early blues, strongly anchored and embellished by jazz musicians from New Orleans, Chicago, and New York. "Big Boy Blues" has a delightful solo by an unidentified tuba player who generates basslines similar to what Coleman Hawkins came up with using a bass saxophone in December of 1925 (see Vol. 3). Much of Rainey's repertoire consisted of songs that dramatized the heartbreaking ups and downs of interpersonal relationships. Near the beginning of "Gone Daddy Blues" Rainey engages in a bit of theatrical patter with an unidentified man who reacts poorly when reminded that she is his wife. "Wife?" he says, "ain't that awful!" Rainey's music was always about real life as she saw it. She sang about battling depression, drinking to excess, and dodging bad prohibition liquor. On a regular basis, her road show background would manifest itself in burlesque entertainment like the famous "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom," a rare example of double entendre lyrics, to which she almost never resorted. The title refers to the Black Bottom, a popular dance rivaled only by the Charleston in its day. The original flipside was a boisterous version of Kerry Mills' "Georgia Cake Walk," with lots of spoken commentary throughout. Most Rainey performances, however, are slow paced diary entries packed with gut-level honesty. Some aspects of womanhood expressed by Ma Rainey are as timeless as can be. In her "New Bo-Weevil Blues," for example, she goes downtown and buys a new hat as a remedy for the blues, explaining to the world in no uncertain terms: "I'm tired of sleeping by myself."