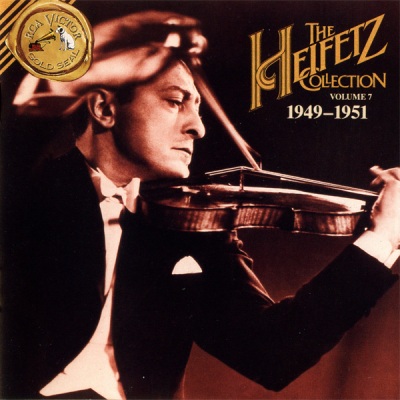

Tha Heifetz Collection, Volume 7 - 1949-1951

Elgar's Violin Concerto is an unusual work in several respects. In substance it is at once expansive and impassioned. It is drawn to a broad scale, with dimensions exceeding those of the Beethoven and Brahms concertos, and to unusual proportions, with its final movement the most extended and most demonstrative of the three rather than the customary brief and lighthearted conclusion. Apart from its personal significance, which has been expounded upon at some length in recent years, it was one of the grand works that marked the belated end of the 19th century in music. The score bears a dedication to Fritz Kreisler, who gave the premiere in London on November 10, 1910 (with the composer conducting) and subsequently introduced the work in various parts of Europe and America. Kreisler, however, never recorded it, and relatively few violinists did until more than a half-century after its premiere. Heifetz did not make his sole recording of the Elgar Concerto until 1949, but by then he had been performing it for years—and had become a frequent participant in English musical life. It was in London that Heifetz made his first recording of any complete concerto, in the very month of Elgar's death, February 1934. The work was the last of Mozart's five concertos, and his associates were John Barbirolli (not yet knighted) and the London Philharmonic, with whom he would record seven more titles (not all of them concertos) within a few years. Later, between 1953 and 1960, he would run up a similar total with Alfred Wallenstein and the Los Angeles Philharmonic; but the conductor with whom he made a greater number of recordings than any other was Sir Malcolm Sargent, his partner in the Elgar. Sargent (1895-1967), like Barbirolli, was especially admired as a collaborator in concerto performances. He conducted for Artur Schnabel in the pianist's pioneering cycle of the Beethoven concertos and over the years worked with numerous other stellar soloists. He was a factor in revivifying the British choral tradition, as conductor of the Royal Choral Society and the Huddersfield Choral Society, and in sustaining a somewhat more specific British musical legacy in his performances and recordings of Gilbert and Sullivan with the D'Oyly Carte company. He not only made more recordings with Heifetz than any other conductor but was the only one to record a given work with him more than once. Their first joint effort (in 1947, the year Sargent received his knighthood) was the Vieux-temps Fifth Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra; another early one was the Bruch G Minor Concerto, also with the LSO; they rerecorded both works in stereo with the New Symphony Orchestra of London. Their Elgar was the second of the nine recordings they made together with those two orchestas in a little less than 15 years. The Tchaikovsky was the only concerto besides the Mozart A Major that Heifetz recorded three times: first with Barbirolli in 1937 and the third time with Fritz Reiner in Chicago 20 years later. His second (1950) was his first recorded venture with the Philharmonia Orchestra and his only one with Walter Susskind, yet another conductor who enjoyed favored status as collaborator with distinguished soloists. Susskind (1913-1980), a native of Prague, earned recognition as a pianist and composer before serving as George Szell's assistant at that city's German Opera, where he made his conducting debut at 19. He managed to get out of Czechoslovakia just before the Nazi annexation in 1939; he settled in London and took British citizenship. By coincidence he succeeded Szell as conductor of both the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow and the Victoria Symphony in Melbourne, and after nine years with the Toronto Symphony he took over the orchestra with which Szell had made his American debut, the Saint Louis Symphony. Susskind is remembered as an effective orchestra builder and for his energetic encouragement of young talent. He founded the National Youth Orchestra of Canada and toured Europe with it; he was also director of the Aspen Festival and School for six years. When he came to St. Louis in 1968 he brought with him as assistant conductor the most gifted of his Aspen students, Leonard Slatkin. In 1975 he settled again in London but returned to the United States frequently as a guest conductor and as musical advisor to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra following the death of Thomas Schippers. The Philharmonia Orchestra was created in 1945 by the recording executive Walter Legge, who was at that time associated with the Gramophone Company. Susskind, who made his orchestral conducting debut that year with the Liverpool Philharmonic, recorded some 200 titles with the Philharmonia. His earlier experience in chamber music, as pianist of the Czech Trio, helped to make him an exceptionally sympathetic collaborator in the recordings he made with such soloists as the soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, the pianists Schnabel, Rubinstein, Solomon and Lili Kraus, and the violinists Milstein, Menuhin and Ginette Neveu, as well as this one with Heifetz. Heifetz made the first of his two recordings of the Saint-Saens Sonata in D Minor with Emanuel Bay in 1952. The warmhearted, expressive work, a product of the same period as the composer's mighty "Organ" Symphony, had been recorded only once before and was a virtual stranger in the recital hall at the time. Heifetz was one of its few champions—and surely the most effective one. The Russian-born Bay (1891-1967), trained at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, was the longest-tenured of Heifetz's accompanists. At various times he served as accompanist also to violinists Milstein, Szigeti, Elman and Francescatti, the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and the singers Helen Traubel and Jan Peerce. After 20 years with Heifetz he was succeeded by Brooks Smith, with whom Heifetz recorded the Saint-Saens in 1967. Heifetz made two recordings of the "Kreutzer," the most extended and most revered of the Beethoven violin sonatas. For the first recording, included in this program, his collaborator was Benno Moiseiwitsch. Moiseiwitsch (1890-1963) also Russian-bom, was one of the last of the famous pupils of the legendary Theodor Leschetizky. He began touring before he reached the age of 20, and lived most of his life in London. He was a virtuoso but not a showman, and was regarded as an elegant performer of the Romantic repertory; his recordings of Rachmaninoff's works rivaled the composer's own, and he made a particularly strong impression in the works of Schumann. This 1951 recording of the "Kreutzer" Sonata was his only collaboration with Heifetz—his only one, in fact, as partner to any violinist. —Richard Freed