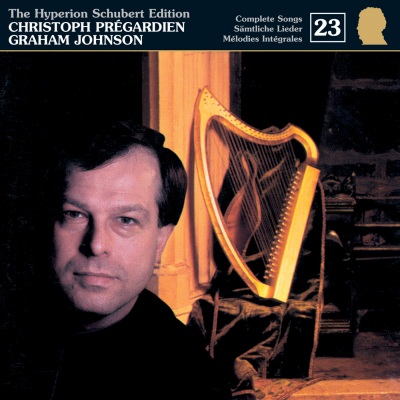

The Hyperion Schubert Edition, Vol. 23: Songs of 1816

Recording details: September 1994 Rosslyn Hill Unitarian Chapel, Hampstead, London, United Kingdom Produced by Mark Brown Engineered by Antony Howell This is the second of two recitals in this series devoted exclusively to the songs of 1816. The booklet accompanying the first of these, the disc by the late Lucia Popp (Volume 17) contained an outline of the documentary information we have for this year. The listener is referred to that essay which attempts to place the songs of 1816 in the context of what we know of Schubert’s biography. Apart from more or less unremitting musical industry, several major events stand out: the unsuccessful application for a job in Laibach (in Slovenia) which would have taken Schubert away from Vienna, Josef von Spaun’s unsuccessful attempt to contact Goethe to obtain his support for an ambitious (and never realized) project concerning the publication of the songs, and, towards the end of the year, a three-fold parting of the ways—from Therese Grob, the love of the composer’s adolescence; from Antonio Salieri who had been Schubert’s teacher for a number of years; and perhaps most significantly, from the composer’s own family—the nineteen-year-old Franz (soon to be twenty) moved out of his father’s school and into the apartment of Franz von Schober. Everything points to a fast-maturing adolescent’s need for independence. 1816 has received rather little publicity as a great song year. It can boast of neither Gretchen am Spinnrade nor Erlkönig which have made 1814 and 1815 so famous in the song calendar. Yet the achievements of 1816 are no less remarkable, particularly in the rather unfashionable field of strophic song which is undervalued today in the light of later more complex through-composed masterpieces. After hearing the two famous Goethe settings named above, which sweep the listener away in torrents of word and tone, one can all too easily forget that Schubert is also revered for his open-hearted simplicity, his economy of means, his clarity and purity, his deference to the poets—all qualities more shy and introverted than those dramatic gifts which announced his arrival to the general public, but which have nevertheless kept him in their minds and hearts. It is interesting that this change to a more reflective, less demonstrative mood in Schubert’s output exactly mirrors the politically conservative mood of the time in Europe. There was neither the brilliant Congress of Vienna (as in 1814), nor the cliff-hanging excitement of Napoleon’s return from Elba, and his final rout at Waterloo (1815). Instead Metternich was set on ensuring that nothing like the French Revolution was ever going to happen in Austria. The police-state instruments of repression were all in place. The days of drama were over and it seems that something in Schubert’s creative personality responded litmus-like to the spirit of the time; Sturm und Drang is succeeded by calme, and, if one knows how to listen for it, the luxe et volupté of a young man dreaming of love and the rosy future. Occasional eruptions like the Stolberg Stimme der Liebe on this disc convince us that the young man still has a great deal of fire in his belly. Maybe he is going through a phase of trying to bring himself under control? For those without the ears to value this quieter, and even old-fashioned, side of the composer, 1816 must seem a step backwards after the glories of 1815. But in reality it was a time of consolidation when Schubert’s literary knowledge was broadened to include some of the greatest German literature (much of it eighteenth-century) available to a budding song-composer. Salis-Seewis is a newcomer for the year and a very welcome one—some of Schubert’s most exquisite miniatures were by this poet. August von Schlegel also makes a first appearance, two years before his brother Friedrich. Jacobi was a poet who belongs to the summer of 1816 alone, as does Uz (both poets inspired some fine songs), and Claudius is largely, though not exclusively, an 1816 poet in Schubert’s output. Settings of Matthisson, Hölty and Stolberg (and of Goethe and Schiller, of course) continue through the year. We should not forget that the Goethe setting An Schwager Kronos is an 1816 work, and in this we hear something of the same thundering conviction as in Erlkönig. A sign of Schubert’s increasing awareness of the social ramifications of his Viennese milieu is his nod in the direction of the poetry of Karoline Pichler and the brothers Heinrich and Matthäus von Collin. Pichler was a celebrated Viennese hostess, and Matthäus von Collin, perhaps touched by Schubert’s Leiden der Trennung (December 1816, to a translation by his dead brother Heinrich) was to play an important part as a link between the composer and the Schlegel circle. In this period between the dissolution of the old school circle and the establishment of that group of adult friends who were to constitute the audience of the later Schubertiads, it is notable that there are no settings by school contemporaries like Kenner and Stadler and only a couple of songs by Schober and Schlechta who were to be a more enduring part of Schubert’s life. Once his independence from his family was finally established the composer was often to favour some of these amateur poets with much greater attention—partially because he was fond of them—but on the whole 1816 is remarkably free of poetry by his friends. Even the war hero Theodor Körner whose poetry was such an important part of the 1815 output does not seem to belong to this new order of peace and stability. An exception to this exile of the amateurs is Johann Mayrhofer who was substantially more gifted than all the rest—and we must give Schubert credit for realizing this. Although the composer had known the poet since 1814 (and had set one of his poems at that time), the first substantial Mayrhofer settings date from 1816. A chronological list of the songs definitely composed in or generally ascribed to 1816 may be found in the book accompanying the boxed set Schubert: The Complete Songs (CDS44201/40—all of Schubert’s songs re-mastered from the original recordings of The Hyperion Schubert Edition into chronological order of composition and three ‘bonus’ discs of songs by Schubert’s ‘Friends and Contemporaries’). Alongside comprehensive indexes, this book contains full song texts and translations, an introduction to the recordings and chronologies of Schubert’s life; it is available separately as BKS44201/40. Graham Johnson © 1995