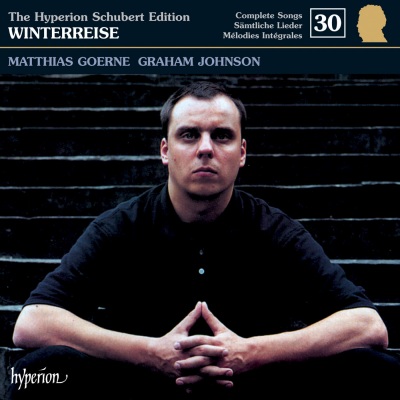

The Hyperion Schubert Edition, Vol. 30: Winterreise

Recording details: August 1996 St George's, Brandon Hill, United Kingdom Produced by Mark Brown Engineered by Antony Howell & Julian Millard The growing popularity of Winterreise in the concert halls of the world, and among singers (increasingly of both sexes, although Elena Gerhardt sang it to universal acclaim as long ago as the Schubert centenary in 1928), would have surprised Schubert’s contemporaries. When they first heard the work they were dismayed, not only by its pessimism and unrelenting melancholy but also by the sparse textures and (when compared to the other songs of Schubert they knew) its lack of charm. The composer himself had seemed somewhat gloomy during the composition of the cycle, so much so that Josef von Spaun asked him what was the matter. ‘You will soon hear it and understand’, the composer replied. Spaun who was certainly the most reliable of Schubert’s friends, both in real life and in the authenticity of his memoirs, continues the story: ‘One day he said to me, “Come to Schober’s today; I will sing you a cycle of spine-chilling songs. I am anxious to know what you will say about them. They have affected me more than has been the case with any other of my lieder.”’ The invitation to hear the songs at Schober’s house was for the evening of 4 March 1827. The fact that Schubert, without excuse or explanation, never appeared at this, his own party, is probably less an indication of his forgetfulness than of his illness (he had had the diagnosis of syphilis hanging over him since late 1822) which, apart from the physical symptoms, induced in him from time to time, not surprisingly, a disturbed and distracted state of mind. In any case, on this occasion, or rather non-occasion, the composer would have been able to play only the first twelve songs of the cycle as we know it. He was convinced that the work was already complete: he had set as many poems as had come to hand. Schubert had found Müller’s texts in the almanac entitled Urania für 1823, where only twelve poems were printed. At that time he was staying with Franz von Schober, and it was almost certainly in that cultured dilettante’s library that the composer had found the small but thick volume (556 pages) which had been published four years previously. (It seems that Schubert was nothing of a book-collector – money was obviously a problem – and many of the volumes of poetry he used for his work were loans from friends.) The wording in Urania is significant: Wanderlieder von Wilhelm Müller – Die Winterreise. In 12 Liedern. This implies that Müller himself regarded the cycle as self-sufficient and complete as it went to press. The trouble was that Schubert was behind the times with Müller’s later outpourings and did not know that the poet had amplified his original conception a year after the printing of Urania, in 1824 to be exact. The fact that Schubert put the word ‘Fine’ at the end of the twelfth song shows that he was unaware that there were further poems in the Müller set. It is also significant that the composer, in this first version of Winterreise, had composed the song Einsamkeit in D minor, as if to bring the cycle, full circle, to a conclusive end in the tonality in which it had begun. Imagine Schubert’s feelings later in the year when he discovered the 1824 edition of Müller’s poems which included a further twelve Winterreise texts, new to him, some of which were interspersed between the lyrics which had already been set! We shall never know whether the composer was overjoyed at finding more poems in the vein that had so appealed to him, or whether he was dismayed that he had embarked on his cycle without realizing that there were further poems in the series. In any case it was immediately obvious that the poet had a very different sequence in mind when considering the work as a whole. This is made clear if we place the order of Schubert’s cycle (as he eventually completed it) side by side with Müller’s sequence. Remember that the composer came across this only in the autumn of 1827: MÜLLER Die Winterreise 1824 1 Gute Nacht 2 Die Wetterfahne 3 Gefrorne Tränen 4 Erstarrung 5 Der Lindenbaum SCHUBERT Winterreise D911 1827 where the first 12 songs follow Müller’s Urania sequence 1 Gute Nacht 2 Die Wetterfahne 3 Gefrorne Tränen 4 Erstarrung 5 Der Lindenbaum So far so good. But now Müller began to interpolate new lyrics (in italics) into the Urania sequence. In so doing he had to recycle four of the original and earlier items which he now placed towards the end of his new, expanded cycle of poems: MÜLLER 6 Die Post 7 Wasserflut 8 Auf dem Flusse 9 Rückblick 10 Der greise Kopf 11 Die Krähe 12 Letzte Hoffnung 13 Im Dorfe 14 Der stürmische Morgen 15 Täuschung 16 Der Wegweiser 17 Das Wirtshaus 18 Irrlicht 19 Rast 20 Die Nebensonnen 21 Frühlingstraum 22 Einsamkeit 23 Mut! 24 Der Leiermann SCHUBERT 6 Wasserflut 7 Auf dem Flusse 8 Rückblick 9 Irrlicht 10 Rast 11 Frühlingstraum 12 Einsamkeit 13 Die Post 14 Der greise Kopf 15 Die Krähe 16 Letzte Hoffnung 17 Im Dorfe 18 Der stürmische Morgen 19 Täuschung 20 Der Wegweiser 21 Das Wirtshaus 22 Mut! 23 Die Nebensonnen 24 Der Leiermann If Schubert now wished his Part One to correlate with Müller’s first twelve lyrics he would have to interpolate settings of four new poems and shunt four songs already completed into the (as yet uncomposed) second half. This would have been highly inconvenient from the point of view of publication plans for the work, which were already in hand at the firm of Haslinger’s. But it was surely more than business expediency that stopped the composer from making a last-minute revision. The way out of the Winterreise problem was a perfect example of the participation of chance, like a turn of the cards or roll of the dice, in determining a new direction. It was the easiest solution, and for that reason some people think that it must have been entirely casual and not thought-out. Schubert simply began his Part Two with the lyrics that he had not already set, and progressed to the end, naturally leaving out the poems that he had already composed. This is probably one of the greatest examples of necessity being the mother of sublime invention, for the line-up of poems which emerged was far superior for his musical needs than the poet’s could ever be. The new order concentrates the dark elegiac poems of Der Wegweiser, Das Wirtshaus and Die Nebensonnen together at the end of the cycle, mitigated by the short, contrasting mood of Mut!. On the other hand, Irrlicht, Frühlingstraum and so on, which break up the screw-turning succession of songs in Müller’s order, belong in Schubert’s Part One; in this earlier position they are not placed to lighten the ever-darkening landscape of the traveller’s mind. It is at the end of the cycle that Schubert suddenly shows that he is, after all, in control of the game, a sign that he was not content to keep without question every card that he had been dealt. He makes one tiny but crucial adjustment to his hand to show us that the ordering of the work is more than the merest fortuitous serendipity: he makes Die Nebensonnen the penultimate song of the cycle rather than Mut!, thus linking the last two items in the matchless hypnotic succession which seems the crowning glory of the work in almost any performance. The fact that he refused to meddle with the integrity of the twelve songs already completed speaks volumes not only as to how satisfied he was with his first cycle (and this includes how one song progresses to the next) but how he regarded it as a finished work in its own right and already something from his past. In fact Winterreise, like that other masterpiece Wolf’s Italienisches Liederbuch, is two separate song cycles, and was published as such in two volumes. The fact that both masterpieces by Schubert and Wolf are regarded by the public, with every justification, as single great works is to do with the power of the composers’ imaginations which weld music together from different periods to make a seamless whole. A glance at Müller’s order shows us that poet and composer had different outcomes in mind for the winter traveller. Müller’s placement of Mut! before Der Leiermann, and the earlier positioning of Der Wegweiser and Das Wirtshaus, suggest a crisis surmounted, a positive re-entry into the world after a lonely journey. One would even say that there is a hint of optimism, that the story is a type of Bildungsroman where disappointment and bitterness are cured by communion with nature, and the man is rendered fit to rejoin his fellow human beings, starting off with the pathetic figure of a hurdy-gurdy player. At how many earlier points of Schubert’s life would he have been sympathetic to this bright-eyed view of the world, personification as he was of man’s endless capacity for optimism and enjoyment of the here-and-now, of Frühlingsglaube – a perpetual faith in spring? But the frightening thing about Winterreise (and it frightened and disturbed the composer too that he should have such negative feelings) was that this faith was no longer there, at least not in 1827. The cycle was composed at a time of coming to terms with his mortality, just as the first Müller cycle, Die schöne Müllerin, was also a cathartic work written in the year that he discovered his sickness. Josef von Spaun described the atmosphere when the Schubert circle eventually heard the completed work: ‘In a voice wrought with emotion, he [Schubert] sang the whole of the Winterreise through to us. We were quite dumbfounded by the gloomy mood of these songs and Schober said he had only liked one song, Der Lindenbaum. To which Schubert only said, “I like these songs more than all the others, and you will get to like them too”.’ If Schubert had come across Müller’s order at the beginning of the year it is probable that he would have set it as it was, but it is also certain that the music would have been different (it would have been an early 1827 work as opposed to straddling the whole year). It is also possible that he would have regarded a twenty-four-song cycle as too great an undertaking at that stage. We owe the shape of the work as it is to a series of accidents, but this is true of many masterpieces and it is not for us to ‘rescue’ and recast the work, and thus deliver it from the fickle but important finger of fate. In doing so we would risk interfering with the hand of the composer. Schubert knew what he was doing. If he was the victim of fate and chance in this matter, or simply a composer unfortunate enough not to have the right book of poems in his possession at the right time, he turned everything to his artistic advantage. Is this not, after all, the least of what we might have expected from a composer–magician of his stature? If we felt, at the end of the cycle, that there was something about it which did not work, perhaps we should have to take the matter into our own hands and re-order the cycle according to Müller. But Winterreise needs no rescue team. It is certain that the majesty and power of this cycle, in countless performances over 170 years, is directly ascribable to the controlling hand of one of music’s most steel-willed, if superficially unassuming, masters. All writers on Schubert’s songs are indebted to what has gone before. English-speaking readers are directed towards the following books which contain commentaries on this cycle: Schubert’s Songs by Richard Capell, The Schubert Song Companion by John Reed, and Schubert – a Biographical Study of his Songs by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Retracing a Winter’s Journey – Schubert’s Winterreise by Susan Youens is by far the most exhaustive study of the cycle in English. Afterword—music in the street, and in the mind Schubert must have heard countless musicians of every kind on the streets of Vienna. His youth was spent in a time of military mobilization and he must have walked in step with many a military band playing their unsophisticated marches militaires. But in this city almost everyone aspired to be a musician. Performers ranged from the relatively sophisticated Bankelsänger who sang popular and topical songs accompanying themselves on harps and guitars to the infinitely less skilled itinerant street-musicians, many of whom were blind, crippled or maimed. These vagabonds, many of them still children, had to make their living somehow. They lined the city walls and hid in dark passages with their harps and guitars, hoping to make a few pennies from striking up in pathetic tones for passers-by. As he walked home to his lodgings, one of which was located in the city walls near the Karolinentor (in late 1826 and early 1827), the composer must often have had these strains ringing in his ears. The topic of street music was an emotive one since long before the time of Schubert, and so it has remained. The dignity of art and indignity of destitution can be a highly uncomfortable combination when confronted in reality and heard at close quarters. It is only the occasional street-musician who gives the kind of musical pleasure which results in money falling in large quantities into his hat; gifted entertainers have a good chance of progressing to a life on the boards. It is far more usual for badly played music to accompany acts of grudging, or embarrassed, compassion. The skeletal figure of Death is sometimes represented playing the hurdy-gurdy in medieval iconography, and it is not surprising that Der Leiermann is often taken to be 'Freund Hain', the figure of Death. Perhaps this is exactly what the poet intended, but as Müller was no musician his choice of ending seems either arbitrary, or eerily pre-destined for Schubert who was no doubt both attracted to and troubled by the poem on a number of levels. This sudden and strangely appropriate mention of a musician, at the last moment in the cycle, may well have been the factor which decided the composer to expand the Ur Winterreise into a twenty-four-song work. Schubert must have been familiar with the problem of penury among musicians who could no longer work, whose talents had been eroded by misfortune and illness. Performing artists and composers, then as now, are self-employed and have to make careful plans for their future. Even a tiny accident can render a player unable to work, and Schubert's hand-to-mouth existence was not protected by such things as insurance and pension plans, much less a Musicians' Benevolent Fund. In ordinary circumstances he need never have feared the loss of his musical capital. After Beethoven's death in March 1827 he must have known that he had inherited the great man's mantle, and had more musical talent in either of his little fingers than anyone else in Vienna—nay, probably the world—but this depended on his fingers being able to function more efficiently than the player of the hurdy-gurdy in Müller's poems. Since 1823 there had been a long and dark shadow across his life: syphilis. This disease had a number of alarming prognoses. Chief among these was that, after a number of years, it was probable that the disease would attack the brain and, with it, the powers of thought and creativity. By 1827 four years had already elapsed and, although he was still in command of all his faculties (to say the least!), there was no telling how long this would last. 'What does the future hold for me?' is a question that must have obsessed him. Whom would it not in similar circumstances? Of course, we know something that he could not foresee—that he was to die within a year of completing Winterreise, spared the effects of tertiary syphilis, still at the height of his musical powers, still composing like a god. But it was really much more likely that, in the normal course of his illness, the river of Schubertian melody would dry up. Perhaps he would be left, like the similarly afflicted Baudelaire, endlessly repeating the same words, parrot-fashion, like a record-playing needle stuck in the same groove of the brain. Can we imagine a Schubert bereft of melody and unable to compose? This was what he expected would be his fate. In the hospital where he wrote part of Die schöne Müllerin in 1823 he had seen the effects of syphilis on patients at later stages of the illness; he had no reason to suppose he would be spared. It was only a matter of time before the fall of the Damoclean sword. It is far too easy to imagine the character of the winter traveller as a self-portrait of the composer himself, denied love and alienated from society; no such autobiographical claim should be made for the cycle as a whole. The winter traveller is in a sense bigger than Schubert himself as King Lear is bigger than Shakespeare. The hero of this cycle achieves an eloquence and stature that are reserved for the mightiest characters in opera. Winterreise is a dramatic event and cannot be explained solely by the sad fate of its creator who was largely able to forget himself and his problems when he was in the process of composing it. As we have seen, many songs in the work refer back to earlier works and can be seen simply as a continuation of Schubert's pioneering achievements in the genre, something quite separate from the special pleading of biographical parallels. But there is documentary evidence that Schubert was shaken to the core in writing this work and that he was strangely moody and withdrawn during its gestation. Of all the songs it is Der Leiermann which might have provoked this reaction. With its barren and bleak landscape it is the only song in Schubert's entire output which is denuded of music itself. There is no real harmonic movement, and the repetitive musical phrases go round in circles. The stumbling fingers of the old man are numb with cold, but perhaps they are also impeded by illness (any musician's nightmare—arthritis, multiple sclerosis, some other neurological complaint—syphilis perhaps). In this way the hurdy-gurdy player on the ice does not seem to be a symbol of death as we usually understand it, but something which, in Schubert's eyes and ears, was far worse—living death, or, in his case, life without real music. One need look no further than the last years of both Schumann and Wolf for an illustration of the protracted period of humiliating disability in the antechamber of death. In the failing music of both these masters' last periods we can detect the chilly grip and numb fingers of the hurdy-gurdy man. Der Leiermann was not drawn from the composer's own experience; the eerie tune was not formed from the large bank of musical allusion and tonal analogue at his disposal throughout the rest of the cycle: nor could the song benefit from the unending fount of melody on which Schubert could draw at any time he chose. For example, the dactylic rhythm of death, a fingerprint which is to be found in Der Tod und das Mädchen and elsewhere, is here nowhere to be heard. Where then does this music come from? The future, perhaps. The composer's future, that is. This song is a moonscape, a projection of an unknown tomorrow. 'What will become of me?' the traveller asks. 'Am I to go with you, hurdy-gurdy man? Will your music be a fitting accompaniment for my poems?' And Schubert allows himself to ask the same thing: 'Will this music be like the music / will compose one day—sans tune, sans harmony, sans everything? Is this how life—my life at least—will come to an end?—a descent into non-music, just like those poor street people who call themselves musicians?' At the beginning of the cycle the traveller could not have imagined himself having anything in common with an itinerant musical beggar, but now ...? How the mighty have fallen! At the beginning of 1822 Schubert would never have believed that he would one day imagine a situation where his own musical abilities might have something in common with the incompetent drone and stumble of a hurdy-gurdy player. On 8 May 1823 Schubert wrote a poem entitled Mein Gebet ('My Prayer') which includes the lines 'Take my life, my flesh and blood. Plunge it into Lethe's flood'. In the penultimate song (Der Müller und der Bach) of the other great Müller cycle, Die schöne Müllerin, the young miller-boy commits suicide by drowning himself in the millstream. The commentary on that work in Volume 25 suggests that, in sacrificing his protagonist and experiencing death alongside the young miller in musical terms, the composer found the strength to continue with what remained of his own life—five matchless years of creativity. This was a cathartic act of self-therapy by someone in extremis, a composer whose artistic survival was in danger of extinction, and who used the most powerful thing he had—his own art—to overcome the crisis. Those who imagine the worst and put it down on paper, even turn it into art, might be thought pessimists and hypochondriacs. But the belief in knowing your enemy, looking him in the eye, and disarming him before the moment of meeting is an ancient one. In Stone Age culture, rock-paintings depicted the successful hunt in anticipation of the event; in medieval times those wishing to be spared the plague simulated its symptoms in a dance of death. Just as Schubert had drowned the miller-boy in his stead, so he encourages the winter traveller to sing non-music with the hurdy-gurdy player; he even composes the non-music for them. As the cycle ends, these two go off together into the distance, and the composer remains behind. In staging the meeting Schubert has not been absorbed or overcome by it. His own ability to write melody has remained intact; in short, he has remained in control. Thus do artists flirt with their own creations, identifying closely with what they are writing but always retaining a distance, a barrier against destruction by what they have called into life. (Mary Shelley's contemporary Frankenstein seems a warning against creators who fail to do this.) Once he had given musical form to his worst nightmare the composer may have felt less frightened by a life destitute of melody, icebound by the winter fog of a degenerative illness. He may even have felt that it was less likely to happen. And in his case, as we know, it never did become reality. This Leiermann remains a powerful and haunting creation, but even if he was the figure of Death he was not given the last musical word. To the traveller's questions 'Wunderlicher Alter, Soll ich mit dir gehn? Willst zu meinen Liedern Deine Leier drehn?' the traveller's answer seems to be an equivocal 'Yes', and the composer's a resounding 'No . A year after completing Winterreise, Schubert penned his final song, the last of the so-called Schwanengesang, on his own terms. This was Die Taubenpost, a miracle of melody, animated with the deepest love. Its beauty is heartbreaking perhaps, but it remains gracefully articulate, unimpaired by any trace of illness or self-pity. Graham Johnson © 1997