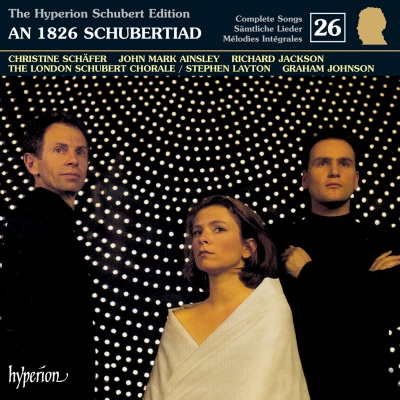

The Hyperion Schubert Edition, Vol. 26: An 1826 Schubertiad

Recording details: February 1996 Rosslyn Hill Unitarian Chapel, Hampstead, London, United Kingdom Produced by Mark Brown & Martin Compton Engineered by Antony Howell & Julian Millard Volume 26 of our Schubert Edition presents a sequence of music which might have been heard at an 1826 Schubertiad and includes songs, ensemble pieces and Schubert’s only melodrama. The four settings D877 from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister are given complete; the first is a duet sung by Christine Schäfer and John Mark Ainsley, the other three Mignon songs by Christine Schäfer alone. John Mark Ainsley sings ‘An Silvia’; Christine Schäfer ‘Hark, hark, the lark’. Other highlights include ‘Nachthelle’ sung by John Mark Ainsley with the Chorale, and Christine Schäfer’s radiant singing of Schubert’s loveliest lullaby, Wiegenlied. The moving ‘Abschied von der Erde’ (Farewell to the World), spoken by Richard Jackson, closes the programme. The first entry for 1825 in Deutsch’s Documentary Biography is from Eduard von Bauernfeld’s diary. It concerns a Twelfth Night party at the home of the painter Moritz von Schwind. The Three Kings in fancy dress played dice in full regalia, and Bauernfeld distributed poems. Schwind was already in the habit of sketching his friends. Thus we are introduced to the circle around Franz Schubert which, due to the absence abroad of Franz von Schober and another artist, Leopold Kupelwieser, is different from earlier years. At this point Bauernfeld, new to the circle, had met the composer only once (in 1822) but after playing piano duets together he was soon to exchange the brotherly ‘Du’ form with him, and drink to friendship. On 7 January a letter from Schwind to Schober (living in Breslau at the time, attempting to pursue the life of an actor) details some of the problems of dealing with Schubert in social situations. Schwind was in love with one of the daughters of the Hönig family and badly wanted to impress her parents, but Schubert was less than co-operative as a companion during an expedition to accomplish this. Schwind also complains that the composer, having promised faithfully to be somewhere, failed on many occasions to turn up (the last thing that seems to have occurred to his friends is that he might have found himself busy with musical matters, or been ill—they put it down to shyness and vagueness); Schubert was also very fussy about where he would and would not go in terms of coffee houses (he was very wilful and was by no means a person to fit in with others at all costs); he was also partial to a bottle of wine, which seems to have helped him relax. Perhaps all this did not make him the best-behaved Leporello for Schwind’s earnest young Don Giovanni. The rather volatile painter mentions a Sunday afternoon spent with Schubert as ‘a veritable calamity’ and Schober later referred to the composer as a ‘naïve barbarian’. On another occasion, however, Bauernfeld (who was not afraid to address the composer as ‘fattest of friends’) refers to him as ‘always the same, always natural’. Schwind later admitted that Schubert’s personality was the catalyst which united the friends into a unified band. In the summer of 1825 he was to write to the absent composer that ‘though each [of the circle] is happy, we are not joyously united without you’. It is clear that Schubert was no longer the happy young man of earlier years, for he had suffered a great deal. In late 1822 or early 1823 he had contracted syphilis, the inevitable further developments of which hung over him like a Damoclesian sword. Indeed John Reed believes that at the beginning of 1825 he suffered a relapse and found himself ill again and in hospital. Even if this were not the case, there was little reason for Schubert to rejoice: he had spent a rather dull summer in Hungary in 1824 where his fondness for the young Countess Karoline Esterhazy could come to nothing; his operatic ambitions had also collapsed and he found himself, at the end of January, just about to turn twenty-eight without any prospects of material success. Perhaps even worse, he had no central relationship in his life and as a syphilitic it was impossible to expect to have one. Little by little the composer had adopted various defence mechanisms to enable him to get on with his work; to those who did not know him well his behaviour might have appeared brusque or eccentric. Schubert could console himself that his songs were becoming well-known in a way that he could not have imagined a few years before. This was mainly because the influential baritone Johann Michael Vogl had brought attention to the Lieder by performing them whenever he was able. On 13 January Die Forelle was published for the second time (it had originally appeared as a supplement of the Wiener Zeitschrift in 1820) and on the evening of the same day Erlkönigwas performed at the Philharmonic Society. When Der zürnenden Diana was published with Nachtstück as Op 36 on 11 February the blurb in the Wiener Zeitung said ‘the excellence of Schubert’s songs is already so generally acknowledged that they no longer need any recommendation’. On 24 February there is an entry in the diary of Sophie Müller, a very gifted actress in the Burg Theatre and a decent amateur singer: ‘Vogl and Schubert with us for the first time today; afterwards Vogl sang several of Schiller’s poems set by Schubert.’ Vogl and Schubert revisited Sophie on 1 March, and the next day Schubert seems to have come alone, accompanying the actress in his own music which, Anselm Hüttenbrenner tells us, she sang ‘most touchingly’. On 3 March Schubert brought Die junge Nonne, and on 7 March, among other things, Der Einsame, a recently composed song which opens this disc. There were further visits to Sophie Müller at the other end of the year. On 6 December, for example, she heard the Lady of the Lake songs. On 8 March 1825 Schubert had contact with a ‘real’ singer, the celebrated soprano Anna Milder who wrote to him from Berlin. It is a typical letter from a diva to a composer: polite deference thinly veils her primary concern of finding material to suit her voice and further her career. He had sent her the score of his opera Alfonso und Estrella (he never got it back) and the saddest news for him in the letter was that no one in Berlin was interested in it. Schubert had admired Madame Milder since he was a boy when he had first seen her as Gluck’s Iphigenia. He no doubt cultivated her in the hope that she could use her influence in the operatic world on his behalf. She was effusive about his gift of the music for Suleika II but added regretfully (and to our minds astonishingly ungratefully) that ‘this endless beauty cannot be sung to the public’. This is a ‘showy’ song by Schubertian standards, with its high notes and tricky piano part, but it evidently still failed to satisfy the singer’s desire for ‘suitable passages and flourishes’. She had to wait for these until Der Hirt auf dem Felsen some years later. (Incidentally, Milder changed her mind about Suleika II and in June wrote to the composer again, saying that she had sung the song ‘after all’ and that it had ‘pleased infinitely’.) A few weeks later (16 April) Marianne von Willemer, Goethe’s ‘Suleika’ and a good friend of Madame Milder, was to write to the great poet mentioning a set of a songs sent to her by a Frankfurt music shop. These were none other than Schubert’s setting of Willemer’s Suleika (‘Was bedeutet die Bewegung?’) together with Geheimes, also from the West-Östlicher Divan. ‘Quite a pretty melody’ writes Marianne to Goethe, but even here the name of Schubert was not destined to appear in his correspondence in a favourable manner, or impinge on his mind. The entry in Goethe’s diary for 16 June of that year is heartbreaking: ‘Consignment from Felix of Berlin, quartets. Consignment from Schubert of Vienna, compositions of some of my songs.’ To the sixteen-year-old Mendelssohn the poet sent a detailed letter of thanks, but Schubert’s songs were ignored. It was the third and last time that the composer attempted to contact Goethe. The delay in issuing Schubert’s Opus 19 (An Schwager Kronos, An Mignon and Ganymed) was probably due to waiting in vain to receive the poet’s acceptance of the dedication. These songs were eventually published in August 1825 without Goethe’s permission, which was fortunately not legally necessary in Austria. From March 1825 an entry in Bauernfeld’s diary shows us that the idea of composing an opera on the subject of Der Graf von Gleichen was born in this month with Bauernfeld as librettist; it was to be the composer’s last opera and exists only in sketch form from 1827. The same diary entry shows that the singer Vogl was far from universally admired in the Schubert circle. Bauernfeld thought he was an affected fop and during a visit to him Schwind behaved with ‘studied rudeness’. Schwind was something of an explosive character, good-hearted but temperamental, and he is the only one of the circle who openly quarrelled with Schubert and fancied from time to time that the composer was laughing at him or deprecating his talents. Through him we see that Schubert had a tetchy side to his nature, and that a certain acerbic bitterness had crept into his behaviour from time to time in the years following his illness. A mysterious insult which offended Schubert during a visit to the Hönig house (Schwind was courting Netti again) was at the centre of one of their tiffs; perhaps this concerned the composer’s illness or his so-called lack of morality. On his side, the composer regarded Schwind as over-emotional, accusing him in one letter of ‘a rigmarole of sense and nonsense’ and ‘brainless chatter’. Schwind was of course also the most gifted of Schubert’s immediate circle of friends and the only one who was to achieve anything like the same level of fame in his own field. Schubert and Vogl got on well enough (they had known each other since 1817) to decide to spend the summer together in Upper Austria. It seems that Schubert had a way of humouring the old singer, allowing him to think he was completely in charge. In return for this forbearance he had Vogl’s advocacy of the songs—interpretations which pleased him better than those by younger artists. This expedition was to be the composer’s most extended holiday, and the first tour of a Lieder duo—although singer and composer had already spent part of the summer of 1819 together in Steyr. Taking with him the manuscript of the recently composed A minor Piano Sonata D845 as well as the Lady of the Lake songs and a quantity of four-handed music, Schubert went off to Vogl’s home town of Steyr in the last two weeks of May. He stayed there for about a fortnight (visiting the nearby monastery of Kremsmünster) and then, after a few days in Linz, progressed from Steyr to Gmunden, a resort thirty miles away in the Salzkammergut, where they stayed for about six weeks (4 June to 15 July). Singer and composer were guests of Ferdinand Traweger who had a young son named Eduard to whom Schubert taught the song Morgengruss (‘Guten Morgen schöne Müllerin’). In 1858 Eduard wrote of these weeks: ‘Hardly was I awake in the mornings when, still in my nightshirt, I used to rush in to Schubert. I no longer paid morning visits to Vogl because once or twice, when I had disturbed him in his sleep, he had chased me out as a ‘bad boy’. Schubert in his dressing-gown, with his long pipe, used to take me on his knee, puffed smoke at me, put his spectacles on me, rubbed his beard against me and let me rumple up his curly hair and was so kind that even we children could not be without him.’ In this house Schubert felt particularly comfortable and remarked more than once that he felt ‘free and easy’ there. He wrote that Traweger senior was ‘a great admirer of ‘meiner Wenigkeit’’ (literally ‘of my littleness’, ‘my humble self’, or just plain ‘yours truly’). Ferdinand Traweger lived until 1909, the longest surviving of all Schubert’s friends. The next port of call was Linz once again where the Lieder duo visited Steyregg Castle and the Countess von Weissenwolf who was a great Schubert enthusiast and to whom the composer was eventually to dedicate his Lady of the Lake songs. We know about this period thanks to letters written to one of Schubert’s oldest friends, Josef von Spaun, by Anton von Ottenwalt—who, incidentally, was the poet of only one Schubert song, Der Knabe in der Wiege composed in 1817. Schubert lodged in the Spaun family home but in the absence of Spaun himself, the Ottenwalts, man and wife, were solicitous companions. To the modern reader Ottenwalt is one of the most sympathetic of the Schubertians. He seems to have understood exactly what a great man they had in their midst, and some of his descriptions of the composer make us feel as if we were there: ‘Schubert looks so well and strong, is so comfortably bright and genially communicative that one cannot fail to be genuinely delighted about it.’ This implies that Ottenwalt knew something of the background to Schubert’s illness. He was obviously the most tactful of admirers in that he delighted in the composer’s company without pushing him into singing for his supper: ‘He has not sung us anything yet, but he has not refused to do so; but he did play the German Dances Marie had practised: they take an incredible life under his hands.’ Both Anton and Marie Ottenwalt provided a haven of supportive admiration for the composer in the days before Vogl joined him to take him back to Steyr. They honoured him for the genius he was, yet they also left him alone as a man in need of a holiday. In this gentle atmosphere of understanding Schubert blossomed. In a later letter to Spaun, Ottenwalt provides us with further riches of perception and empathy: ‘We sat together until far from midnight, and I have never seen [Schubert] like this, nor heard: serious, profound and as though inspired. How he talked of art, of poetry, of his youth, of friends … I was more and more amazed at such a mind.’ This is perhaps the only time we read of one of Schubert’s contemporaries saluting his mind as much as his music. Ottenwalt refutes the myth common among many of the circle (and still a part of the misconceptions surrounding the composer’s talents) that Schubert was scarcely conscious of his own artistic achievements: ‘I cannot tell you of the extent and unity of his convictions … there were glimpses of a world-view.’ And neither was Ottenwalt unsophisticated. He realized that Schubert was sexually complicated and that his personality, full of contradictions, balanced out into something unique: ‘His works proclaim a genius for divine creation, unimpaired by the passions of an all-consuming sensuality, and he seems to have truly devoted sentiments for his friends.’ Schubert’s own letter to Spaun from Linz (21 July 1825) expresses his exasperation with the heat (later he wrote ‘I grew positively thin from perspiration’) and also his sorrow that Spaun himself is not there. The two men were very old friends from the composer’s early schooldays; Spaun referred to Schubert as ‘Bertl’. We also learn from this letter that Schober intended to return to Vienna after his attempts to become an actor. Schubert cannot resist a behind-the-back dig at his friend whose plans to tread the boards had only resulted in minor success: ‘Punchinello’ … is said to be his star part. Rather a steep descent from the heights of his plans and expectations!’ Is there a trace of bitterness here that could go back to the origins of the composer’s illness? Had Schubert felt abandoned when Schober’s decided to leave Vienna in 1823 when the composer needed close friendship more than ever before? Back in Steyr between 25 July and 15 August Schubert wrote a long letter to his parents, the first of a series of important documents from this summer which allow us to glimpse the composer in a sharper light. This letter is in part an itinerary of the holiday so far, together with certain pieces of career information designed to reassure those at home who anxiously wait for news of the young man’s advancement in the world. Thus we learn that the Scott songs from The Lady of the Lake (including Ave Maria sung by Vogl) had not only been a great success with everyone, but that it was planned to issue them bilingually with English texts as part of a plan to establish the composer’s reputation in England (Schwind had hoped to do the same with his drawings based on Der Freischütz). Schubert speaks of his own attitude to religious music and, as someone less than fervent in his attachment to the church, manages to remain honest (‘I have never forced devotion in myself … unless it overcomes me unawares’). At the same time he satisfies the folks at home (who are fervent believers) that his music ‘grips every soul and turns it to devotion’. We read here of Schubert’s visits with Vogl to the monasteries of St Florian and Kremsmünster where he found his music already known and enjoyed. Here too he had an audience of connoisseurs which gives rise to the most important thoughts about piano playing that have come down to us via his letters: ‘Several people assured me that the keys become singing voices under my hands, which, if true, pleases me greatly, since I cannot endure the accursed chopping in which even distinguished pianoforte players indulge and which delights neither the ear nor the mind.’ The letter ends with enquiries about his brother’s health. We learn that Ferdinand Schubert was well-known in the family as a hypochondriac and Franz, who had so much more to fear in terms of his own health, pours gentle scorn on someone who is frightened of death. ‘As though dying is the worst that can happen to us humans!’ he writes, and then, almost casually, adds some of the most moving words he ever wrote: ‘If only [Ferdinand] could once see these heavenly mountains and lakes, the sight of which threatens to crush or engulf us, he would not be so attached to puny human life, nor regard it as otherwise than good fortune to be confided to earth’s indescribable power of creating new life.’ Many dark hours of contemplation in the previous years must have been behind this single sentence. Schubert’s sentiments in this letter seem closer to Buddhism than Christianity. A letter from Schwind to Schubert (6 August) tells of how Schober, always with an eye to the main chance, has been attempting to interest Ludwig Tieck, newly appointed dramaturge in Dresden, in Alfonso und Estrella (the libretto by Schober of course). Apart from a sketch of a song (Abend, D645, 1819) this is the only time that Schubert’s life obliquely brushes that of Tieck, a great romantic poet and writer. At exactly the same time in Vienna, Franz von Bruchmann was once more in contact with the poet Platen (they had known each other since 1821). Platen already knew two Schubert settings of his words (Die Liebe hat gelogen and Du liebst mich nicht later published as Op 59 in September 1826) and was impatient for more. There were to be no further Platen songs, however, and the composer was to have no personal contact at all with perhaps the most important of the German poets to express admiration for his work. The estranged Bruchmann was obviously in no mood to act as Schubert’s go-between. On 15 August Schubert and Vogl set off on the journey to Bad Gastein. This took three days (via Kremsmünster, Neumarkt and Salzburg) and encompassed the most spectacular scenery the composer was ever to see. A month or so later Schubert sat down and attempted to write a travelogue of this journey for his brother Ferdinand (whom he knew was especially interested in topography). This ran into two ‘instalments’ (the second on 21 September) but it was never finished. Nevertheless these two letters are moving documents of Schubert’s reactions to all the sights and marvels of nature. It is here that he also comments on his pioneering work as a collaborative pianist: ‘The manner in which Vogl sings and the way I accompany, as though we were one at such a moment, is something quite new and unheard of for these people.’ Not only for those people, one might add, but for the whole world of music, for this journey established a new genre of music-making: by taking these Lieder out of the context of the Viennese salon there dawned an awareness of the wider demand for this music, and even the commercial possibilities of this type of tour. It would have been the first of many such journeys had the composer lived longer. In Salzburg Schubert was moved to tears at the grave of Michael Haydn, whose music he knew well from his schooldays. Although he adored the surrounding scenery he found the city itself dark and foreboding and, as is so often the case in summer, spoiled by rainy weather. Once the pair had reached Gastein Schubert was amazingly creative. Re-acquaintance there with the distinguished cleric Ladislaus Pyrker, Patriarch of Venice, led to settings of that poet’s Das Heimweh and Die Allmacht. He also composed the Piano Sonata in D major, D850, and continued work on a symphony. For nearly a century, scholars believed in the existence of a large orchestral work composed that summer, the score of which had been mysteriously lost. Known as the ‘Gmunden-Gastein’ symphony, it is now established, largely thanks to John Reed, that this was none other than the ‘Great’ C major Symphony. With aural hindsight we can hear in this work musical parallels with the epic scale and dramatic sweep of the scenery of Upper Austria. On 4 September Vogl and Schubert began their journey back to Gmunden where they stayed until 10 September. They then returned to Steyr and spent a few more days in Linz at the end of the holiday. Vienna was now calling to Schubert particularly because he knew that he would find there not only Franz von Schober whom he had not seen for two years (‘a man whose plans have miscarried’, Schubert remarks wryly in a letter to Bauernfeld) but also the painter Leopold Kupelwieser to whom he had poured out his heart about his illness in a letter to Rome in 1824. In actual fact Kupelwieser’s devotion to his fiancée (later his wife) Johanna Lutz, and to painting were to take him away from the gatherings of the bachelor Schubertians which now often consisted of drinking until two or three in the morning. An entry in Bauernfeld’s diary in October 1825 says ‘Schubert is back’, but the old days of young, uncomplicated friendship were gone for ever; there was something less cosy about the new wave of Schubertians. This feeling of instability may have been the result of Schwind’s restless temperament, Schober’s vacillations which sometimes (according to Bauernfeld) verged on folly, and Bauernfeld’s own up-and-down nature. Vogl had gone to Italy in the meanwhile to spend the winter there. Perhaps the most joyous period in Schubert’s life was at an end; the summer journey had afforded him unsurpassed happiness. The autumn was hardly auspicious with various projects which came to nothing, although there could be no doubt Schubert’s fame was growing. In December 1825 the Wiener Zeitung advertised copies of the Rieder portrait of Schubert (an ‘extremely good likeness’) for sale; this blurb refers to ‘the composer of genius’ and to Schubert’s ‘numerous friends and admirers’. It was during this month that he composed most of the settings from Ernst Schulze’s Poetisches Tagebuch (sung by Peter Schreier in Volume 18). Some of these were performed for Sophie Müller on 25 January 1826. 1826 began with a party on New Year’s Eve. Schubert was not present. Whether he was ill or perhaps too taken up with the composition of lyrics from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister is impossible to say; he probably pleaded illness more than once to excuse himself from gatherings. For this occasion Bauernfeld had written a short play, based on the Schubert circle, to be read after midnight. It sounds very laboured by today’s comic-sketch standards, and its in-jokes would have been comprehensible only to the assembled company. Schubert is assigned the role of Pierrot and depicted as lazy (a very common misconception that was to persist until the world at last saw the size of his output), happy-go-lucky, and fond of amiable chortling. Schober (Pantaloon) is depicted as a rather dissolute ladies’ man and also lazy. We find the name of Johann Gabriel Seidl in a letter from 10 January when the twenty-two-year-old poet is bidden to a ‘feast of song’—obviously a Schubertiad. Schubert had known Seidl since 1824 when as an ambitious twenty-year-old the poet had asked him to provide music for his play Der kurze Mantel. Schubert had agreed to do so but had let Seidl down. To make up for this disappointment Seidl could rejoice that his poetry was much to occupy Schubert in 1826; he became one of Schubert’s ‘selected’ poets to whom he returned many times (like Schulze some months earlier) and some of the composer’s most ravishing songs composed in March 1826 are to Seidl texts. The Goethe setting Rastlose Liebe was performed at the Philharmonic Society on 12 January. On 14 January there was a ‘sausage ball’ (where the gentlemen served this delicacy to the ladies no doubt faute de mieux) for which the composer provided waltzes. At the end of the month there were two rehearsals for the D minor String Quartet (‘Death and the Maiden’) during which Schubert corrected the parts and even cut a section of the first movement. This was for a performance at the home of Joseph Barth at the beginning of February. The work had been composed substantially in 1824. On 31 January (the composer’s twenty-ninth birthday) he was paid a reasonable, if not spectacular, amount of money by the publisher Artaria for his D major Piano Sonata and the piano duet Divertissement à la hongroise. On 3 February the youngest of Schubert’s brothers, Anton Eduard, was born. Franz Schubert senior was obviously still hale and hearty; indeed he received the freedom of the city of Vienna as a reward for forty-five years of service as a schoolteacher and for charity work in the community. At this point different Schubert songs were being performed frequently at Philharmonic Society concerts, and there was a spate of song publications including the Op 52 Lady of the Lake songs which had been such favourites throughout Upper Austria the previous summer, as well as a number of Schiller songs. Also issued was Op 57 which included settings by Friedrich von Schlegel and Hölty. The Swiss publisher Nägeli was soon to ask for a Schubert piano sonata through the offices of Karl Czerny. The time had come when Schubert, becoming more respected a name in the musical world with each passing week, attempted to put his finances on a more stable footing by applying for the vacant post of Vice-Kapellmeister of the Imperial Chapel. With his application Schubert enclosed a reference by Salieri which had been written in 1819. The post was eventually awarded to the composer Josef Weigl; at least Schubert admired him and did not resent his success. It was perhaps just as well that Schubert did not enter the establishment proper as he was far from being a supporter of the government. The repressive side of Metternich’s police state was emphasized in April when the authorities, terrified of the intelligentsia fermenting unrest among students, raided the meeting of ‘Ludlamshöhle’ (‘Adullam’s Cave’, see 1 Chronicles 11: 15) which was nothing more than an innocuous Davidsbund, an anti-philistine society of artists, writers and what would later be termed ‘bohemians’. Schubert and Bauernfeld had both applied for membership of this organization; if they had done so earlier they might have been subject to the unpleasant interrogation and detention suffered by a good many of Vienna’s artistic élite, including the playwright Grillparzer. The composer had already had an unpleasant experience with the police in 1820. Infinitely better than working as a musical civil servant would be a success in the opera house; this had always been Schubert’s dream and he had tasted this sort of celebrity in a small way in his earlier years. There was a new Director of the Court theatres, Ignaz von Mosel, who admired Schubert’s songs and had been the recipient of a letter from the Leipzig poet and critic Rochlitz about Schubert’s excellence as a composer. It was agreed between all concerned that Bauernfeld should provide a libretto based on Der Graf von Gleichen and that Schubert should set it. The poet went on holiday to Carinthia in the early summer where he worked on the libretto which the composer awaited with impatience. Back in Vienna Schubert was in the doldrums, partly because of the weather (‘the sun simply refuses to shine. It is May and we cannot sit in any garden yet. Awful! Appalling! Ghastly!!! And the most cruel thing on earth for me!’). Bauernfeld’s holiday companion was a young army officer named Ferdinand von Mayerhofer. This name has no connection with the poet Johann Mayrhofer, but by coincidence that most important of poets in Schubert’s earlier career emerges briefly from the shadows at this time: he went on a cure to Karlsbad together with Anton von Spaun (one of Josef’s brothers) and subsequently briefly re-established contact with his former friends. The major (and unexplained) rift between Schubert and Mayrhofer had been some years before. Another return to the fold was that of the singer Vogl who came back from Italy and astounded everyone with the announcement that he was to marry one Kunigunde Rosa; no one had believed that he was the marrying kind. It is said that at this time Vogl encouraged Schubert to apply for the position of coach at the Opera House. The rather unreliable Anton Schindler (Beethoven’s friend) has left us with a gossipy account of Schubert’s inflexibility and anger when confronted with the behaviour of a young diva who thought the orchestra too loud for her voice: he apparently stormed out of the theatre in a rage. It is not the only story of this kind which shows the composer’s touchiness when he was challenged by musical inferiors, who included, after all, the whole of Vienna’s population with the exception of Beethoven! It was at this time that Schubert’s name appears in the older composer’s conversation books where one Karl Holz tells Beethoven that Schubert ‘has great powers of conception in song’. It seems that, some months before, Schubert had heard and praised the first performance of Beethoven’s Op 130 Quartet in B flat as well as the ‘Archduke’ Trio with the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh whom Schubert knew well. Perhaps this was the inspiration for another masterpiece, for the younger composer was soon to finish (30 June) his own great G major String Quartet, D887, arguably the single most important work of 1826. Instead of a proper summer holiday Schubert spent some time outside Vienna at Währing (together with Schwind) in the home of the Schober family. It was there that he composed his Shakespeare settings in a little book with pencil-drawn staves. He would have liked to re-visit the sites of the previous enchanted summer in order to see his absent librettist but on 10 July he wrote to Bauernfeld: ‘I cannot possibly get to Gmunden or anywhere else, for I have no money at all, and altogether things go badly with me.’ Schubert had arrived at that stage which tormented Mozart and which still troubles many young artists for a period: his fame exceeded his fortune. In this transitional phase of a career it takes a few years for financial status to catch up with reputation. Nevertheless he added: ‘I do not trouble about it, and am cheerful.’ When Bauernfeld returned by boat to Vienna at the end of July the composer was there to meet him at the landing-stage. ‘Where is the opera?’ asked Schubert. ‘Here!’ the poet replied, and handed him Der Graf von Gleichen. Sadly, the subject-matter of the work, which concerned the bigamy of the eponymous hero, fell foul of the censors. Schubert remained determined to compose it, but it was inevitable that the project should somewhat lose its appeal for him. The extant sketches (which were first published in facsimile in 1988) date from 1827. In August Schubert decided to launch an ‘attack’ on the German publishing houses in the effort to interest them in his music. He wrote almost identical letters to the houses of Probst and Breitkopf & Härtel listing the works he had available for publication (‘You may take your choice among songs, string quartets, pianoforte sonatas, 4-handed pieces, &c. &c. I have also written an Octet.’). Probst replied that, ‘Our public does not yet sufficiently and generally understand the peculiar, often ingenious, but perhaps now and then somewhat curious procedures of your mind’s creations’. The publisher wanted ‘easily comprehensible’ pieces to be sent to him. The reply from Breitkopf & Härtel was loftier still and treated Schubert like a beginner, effectively asking him to send pieces without expecting payment. They were to make handsome amends only sixty years later when this firm embarked on the engraving of a complete edition of the composer’s works in thirty-nine volumes. Apart from the composition of Seidl’s Nachthelle for tenor, chorus and piano, the most important event in September seems to have been the marriage of Leopold Kupelwieser to Johanna Lutz. Schubert provided the dance music for the assembled guests (a role he often assumed for his friends’ gatherings as a sort of living radio or gramophone). In October Schubert dedicated his C major Symphony to the Philharmonic Society and handed over the autograph; in return he received an honorarium of 100 florins. It was also a busy month for music with the composition of two substantial works: the G major Piano Sonata D845 and the Rondo in B minor for violin and piano D895. Towards the end of 1826 and well into 1827 we have a special insight into the activities of the Schubertians, thanks to the presence at the gatherings of two brothers Fritz and Franz von Hartmann, friends of the Spauns in Linz. Although they were marginal figures as far as Schubert was concerned, the diary of Franz is invaluable in capturing the mood of the Schubertiads at the end of this year. It gives us an idea of the frequency and vivacity of the circle’s social life which was never so meticulously chronicled as it was for this short time by Hartmann. We learn about a new inn, The Green Anchor, where the friends habitually gathered. They were there on 17 November, on the 19th, again on the 21st and yet again on the 25th and 30th. On only two of these occasions is the presence of Schubert mentioned. The Hartmanns pronounced Schober ‘quite interesting’ and Bauernfeld ‘very dull’. They were of a different generation than most of the men with whom they kept company (eleven years younger than Schubert) but they came from a musical family and seemed to appreciate the music they heard. This pattern of late nights drinking at The Green Anchor or Bogner’s Café nearby continued into the next month. On 8 December there was a Schubertiad at the home of Josef von Spaun where it is possible that Schubert played a portion of his G major Piano Sonata which was dedicated to the evening’s host. Fritz Hartmann found this music ‘magnificent but melancholy’. Schwind, it seems, was capable of singing Schubert songs, and he did so with the composer. With a note of relief Fritz von Hartmann writes: ‘At last everybody began to smoke.’ On 15 December there was a ‘big, big Schubertiad’. The guest list included Witticzek, Wasseroth, Kupelwieser, Grillparzer, Schober, Schwind, Mayrhofer, Bauernfeld, the pianist Gahy (Schubert’s preferred four-hand partner), the poet Schlechta and many more. Vogl sang no fewer than thirty songs. The music was followed by dancing and at about 12.30 a.m. the ladies were seen home. Some of the men then repaired to The Green Anchor, including Schubert himself, Schober and Schwind. It was this occasion that probably formed the basis of Schwind’s sepia drawing of 1868 entitled ‘A Musical Evening at Josef von Spaun’s’, although this famous work was a composite of many occasions in the artist’s memory and it is unlikely that all the guests depicted were ever under the same roof at the same time. There seems to have been in this winter a sense of intoxication in this group of people, an enthusiasm fed and heightened by Schubert’s music; on the following night there was yet another Schubertiad, albeit on a smaller scale. On the next day, Sunday 17 December, there was an all-day party which started at breakfast time and went until 11.30 p.m. In the afternoon Schubert himself sang (Der Einsame and Trockne Blumen from Die schöne Müllerin) and there were also gymnastic displays and conjuring feats. Everyone brought their own talents, such as they were, to these gatherings, although we know that older members of the circle, including the composer himself, thought that the meetings had become too rowdy. The day ended at The Green Anchor as usual. On the Monday evening (18 December) there was another gathering with Schubert’s music, this time at Witticzek’s. 19 December was reserved for a visit to the theatre to see Kleist’s Kätchen von Heilbronn starring the famous actors Heinrich and Emilie Anschütz with whom Schubert had spent Christmas Eve in 1821. Schubert was now living alone (rare for him) right on the edge of the inner city on the so-called Bastei. Franz von Hartmann accompanied Max von Spaun (known as ‘Spax’) to Schubert’s apartment ‘through the most frightful mud’ but did not go up with him to see the composer. This confirms that Schubert was not free and easy and accessible to all. Far from it. Young Hartmann simply did not know the composer well enough to visit him at home. On 21 December there was a concert at the Philharmonic Society which featured Beethoven’s Quintet Op 29 as well as music by Romberg, Kreutzer, Rossini and Randhartinger. Schubert was represented by his song Der Zwerg which was performed twice. There was a party afterwards, at The Anchor of course, and Schubert’s presence is noted. It would be interesting to know how the composer spent Christmas itself. Almost certainly he returned to his family, and there is a break in Hartmann’s diary at this point. There was another concert at the Philharmonic on 28 December which included a Haydn quartet, arias by Meyerbeer and Rossini, and a ‘Miss Griesbach from London played the harp’. No Philharmonic Society concert now seemed complete without a Schubert song and on this occasion Die junge Nonne was sung by one Karoline Schindler. The year continued to its end with convivial gatherings but no more music. On 30 December there was a great deal of reminiscing at The Anchor about life at the Seminary where Schubert had been a pupil with Spaun. Afterwards there was a game of snowballs where ‘Spaun gloriously protects himself against the shots with his open umbrella’. Here the young Hartmanns were encouraging much older men to behave like schoolboys, and no doubt the amount of noise in the street was disturbing to the burghers of Vienna. Schubert took no part in the fight, probably not feeling fit enough to do so after a heavy Christmas of eating and drinking. On New Year’s Eve there was a much quieter party at Schober’s house where, at the stroke of twelve, glasses were filled with Tokay and everyone’s health was drunk. Schubert was present, and the gathering broke up at 2 a.m. The composer now found himself in the second-last year of his life. Graham Johnson © 1996 详细