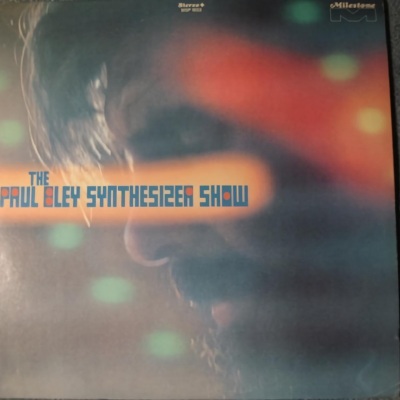

Synthesizer Show

by Eugene Chadbourne It doesn't seem right to use the term avant garde in relation to a tune as downright pretty as Annette Peacock's "Mr. Joy," which kicks off this often maligned early-'70s Paul Bley effort. Sometimes this term is assigned for life just because it was used at the time of the recording. In a sense, the early players of prototype synthesizers or other newly developed musical equipment are perhaps the only real avant garde musicians. This philosophy would be one of those concepts in which the actual sound of the music is deemed irrelevant. What it actually sounds like when a listener tunes into the Paul Bley Synthesizer Show is quite varied, but be sure to get ready for plenty of tone settings that sound like a Muppets toy keyboard, and that's a compliment. Considering the legendary horrors of getting this early electronic equipment to work on tour, it is no surprise that these studio recordings are much more successful approximations of what Bley and his partner, Peacock, were striving for. Another big difference with the European tour involving this couple and these instruments that came along just a bit later was that Han Bennink was enlisted to play drums overseas and handled the situation completely differently. Bley's monophonic keyboard, no matter how mightily it might squiggle, was no match for Bennink. The drummers featured here play more in the manner of a typical drummer in a Bley piano trio, meaning quietly and with much space, and there are even a pair of acoustic piano trio numbers included to boot. This approach to percussion means the synthesizer doesn't have to compete to be heard, leading to some really marvelous moments of barely audible high pitches on "The Archangel." Rhythm section playing is particularly good throughout the recording, even in the case of musicians such as bassist Dick Youngstein and drummer Steve Haas. The rhythm section of bassist Frank Tusa and drummer Bobby Moses also contributes a lot of really beautiful playing, the drummer shifting rhythms delicately and playing a terrific solo on "Snakes." All the drummers featured have an uncanny knack of knowing when to lay out, and not only in deference to the subtle dynamics of electronic music. The acoustic performance "Gary" is wonderfully slow and spacy. Jazz critics made toast of this release when it originally came out, and when the electronic sounds featured lost their original novelty it did little to add value. Despite interesting moments of sound experimentation, most of the time Bley uses the synthesizer simply to play sweet sounding melodies, so his electronic work can hardly be considered some kind of radical innovation. Several of the tunes such as "Parks" are more like stuff Les McCann came up with, but without that artist's innovative keyboard overdubbing. Removed several decades from the initial hoopla about electronic instruments, this music can really be appreciated as a stunning document of Bley in action, bringing past and present aspects of his creativity into something new, developing right in front of the musicians that he gets such superb performances out of.