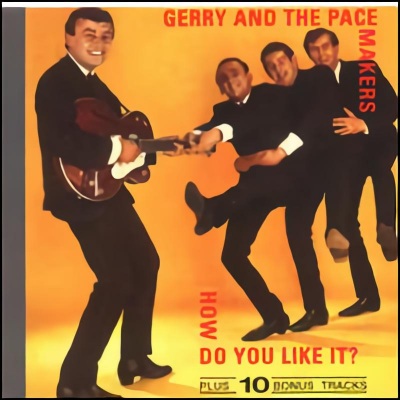

How Do You Like It?

by Bruce EderGerry & the Pacemakers' debut album, produced by George Martin and Ron Richards, is representative of the mainstream Liverpool sound beyond the Beatles, circa 1963. Gerry & the Pacemakers based their music around American R&B ballads, coupled with a delight in straight-ahead rock & roll and country music with a beat, in a manner similar to the Beatles. Gerry Marsden was a fairly powerful singer and a more natural (but not necesarily better) rock & roll guitarist than George Harrison, as revealed by his crunchy playing on numbers like "A Shot of Rhythm and Blues," "Jambalaya" and "The Wrong Yo-Yo," and his lively solo on "Maybelline" -- the problem was that neither he nor the rest of the band could match the Beatles for style. Drummer Freddie Marsden, despite much quicker hands, wasn't nearly as distinctive as Ringo Starr, and Les Chadwick's bass work was weighty, but not a third as interesting as Paul McCartney's, and Gerry's singing never came close to Paul's. When you add in the fact that their in-house songwriting was almost nonexistent here, and their backing harmony vocals were a shadow of what the Beatles could produce, the result is a more limited quantity; How Do You Like It isn't as good an album as Please Please Me or With the Beatles, but it also reveals a band that was already 85% as interesting and complex as it was ever going to be. On the other hand, the group does rock out, which is all they really ever set out to do, and on those terms they're pretty engaging -- their covers of Hank Williams' "Jambalaya," Larry Williams's "Slow Down" and the Piano Red/Carl Perkins number "The Wrong Yo-Yo" are more than a little diverting, good examples of the classic thumping Liverpool sound that and their version of the Arthur Alexander number, "Where Have You Been," is moving and passionate, if not as well sung as the Searchers' rendition. And as the T.A.M.I. Show revealed, Chuck Berry didn't mind jamming with Gerry on "Maybelline." The 1997 EMI 100th Anniversary edition, remastered in 20-bit digital sound, is close and loud, and features both the stereo and mono versions of the album -- the mono version is punchier and more enveloping, but the stereo has its virtues, separating the voices and instruments binauraly, as was the custom in those days, which allows the listener to pick them apart, if anyone wants to analyze Gerry's guitar, Freddie's drumming, or Les Maguire's piano playing that closely; it's a reminder of what EMI is not permitting us to do with the Beatles' first two albums and early singles.