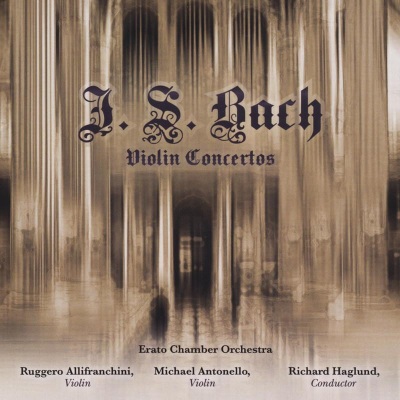

J.S. Bach: Violin Concertos

Residing in Leipzig since 1723, in 1729 Bach became director of the Collegium Musicum, which had been founded by his colleague, Georg Phillip Telemann. At that time there was no such thing as a public concert. The Collegium Musicum was a private society started by university students who were active musically. They performed two-hour concerts twice weekly in a coffeehouse. Bach’s violin concertos were probably written for and performed at those concerts. By the time Bach joined the Collegium Musicum he had written a huge number of church cantatas, far more than would ever be needed for all the church services of the year. The Collegium Musicum thus represented an opportunity which he had never had before, of composing not out of the obligation but for fun – even if he had to write out every orchestral part himself, which he did, unless he could corral one or another of his numerous sons to do the tedious job. The musicians who played his concertos and solo pieces for violin must have been of very high caliber. (Bach himself had plenty of instruction on the violin, but none on keyboard, even though he became famous as an organ and harpsichord virtuoso.) But what especially stands out in the concertos, especially the on in E Major, is the overwhelming sense of vitality and bubbly, unquenchable joyfulness. Just as Mozart’s operas were written for specific singers, Bach must have had particular violinists in mind, and he wrote to suit them. Both their names and the precise dates of the performances have been lost to history. The time and effort he spent arranging the programs of the Collegium Musicum soon produced chastisement from his church employers; he was neglecting his teaching duties, sometimes abandoning them. But chamber music was so much more fun! And he got to escape, for a while, the petty policies of his church committees, the bane of his existence. However, he eventually brought everything he learned from his experiments with the Collegium Musicum into his church music, which he never ceased writing. His sons, also felt it was felicitous to have their own experiences in the society on their resumes, when they applied later for music jobs. The Bach Double Concerto may first have been played by Bach’s two oldest sons; with Bach conducting from the harpsichord, this concerto would have been a true family affair. Unlike nineteenth-century concertos, which often depict a battle between soloist and orchestra, the Double is almost nothing but congeniality and cooperation between the parts, and one has to dig deeply to find a trace of sibling rivalry or other psychological dissonance described, it is there at all. Woody Allen, however heard enough intensity and strife in the melodic material itself to use the first movement in his movie, “Hannah and her Sisters”, introducing the first antagonist, the younger sister who would embark on an affair with the husband of her sister Hannah, upsetting the family’s happy apple cart, so to speak. It was in the concerts of the Collegium Musicum that Bach became well-acquainted with the concertos of Antonio Vivaldi, undoubtedly including The Seasons, which are also recorded by Antonello. Much speculation has been written on the influence of Vivaldi on Bach, but there is no absolute proof of what the influence was. The speculation is based on a statement Bach made to one of his sons, that Vivaldi “taught him how to think musically.” This statement is intriguing because all of Bach’s music, even that from his formative years, is of very high quality, and second, the consensus of the ages has always been that Bach is the greater composer. Christoff Wolff, professor at Harvard, has written a long essay on the subject, and what Bach’s surprising statement might refer to. Bach spent his entire life studying and transcribing other composers’ music, with special study devoted to the Vivaldi violin concerti. Bach transcribed many of Vivaldi’s violin concertos for solo harpsichord so he could study them at his leisure. Bach recognized that the initial musical ideas which launch each of Vivaldi’s compositions drive the entire musical composition; everything grows and develops out of that first idea, and subsequent ideas give birth to more ideas, and so forth and so on, the listener can hear and feel that they only work in that order. In contrast, the musical ideas of vocal music unfold in the other that is determined by the words and story, and not the purely musicals ideas. This particular type of writing, where the ideas generated are purely musical (as opposed to ideas from lyrics), made for a great change in the history of music. From then on, instrumental music, as opposed to vocal music, would dominate the musical scene and the composers who could best manipulate purely musical ideas would be considered the greats. This was a change from before, when the ability to put words to music (principally biblical texts) was considered the greatest test of talent. Bach felt that this change in musical history, which he desired to be part of, was sent in motion by Vivaldi. The Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV1068, came to be known as the Air on the G String after movement was transposed and rearranged for solo violin with piano or orchestra. Bach composed his four orchestral suites when working for Prince Leopold in Kothen, who preferred secular works to the church music that Bach was accustomed to writing. The Air is the first piece of Bach’s ever to be recorded, in 1902 with the cellist Alekandr Verzhbilovich and an unknown pianist. Here it has been re-arranged by Peter Arnstein for solo violin and string orchestra, back to the original key of D Major. -Notes by Peter Arnstein