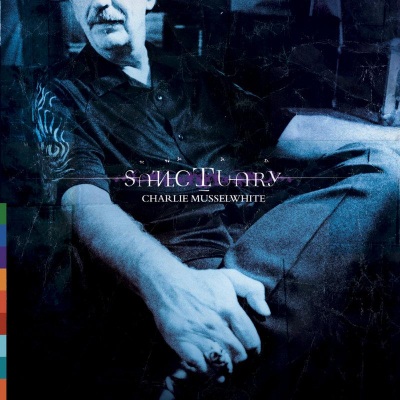

Sanctuary

by Thom JurekOn 1999's Continental Drifter, king harmonicat Charlie Musselwhite began stretching the boundaries of his Delta blues' heart to embrace music that encompassed the emotional and organic range of blues music without adhering to a strict formula. In that case, it was Cuban son; on 2002's One Night in America, it was roots country and Americana. In both cases, the blues were the root and the destination, but by winding in these other sounds, Musselwhite's blues heritage became more, not less organic; it was more deeply rooted in the soul of the Americas at large. On Sanctuary, Musselwhite's reach extends back to the blues from the Mississippi Delta, but his pedigree reveals the blues tradition as the true signifier of all American music, whether that music is grown from the soil itself and projects itself to the ends of the earth, or reflects its image back across the distances to the homeland, or into a mirror. Inside that tradition is the cornerstone, the "sanctuary" for all modern popular music to claim as its root. Issued on Peter Gabriel's Real World label, Musselwhite has assembled a crack band for this outing: Joined by guitarist Charlie Sexton (formerly of the Bob Dylan band), bassist Jared Michael Nickerson (Gary Lucas, Freedy Johnston, Jeff Buckley) and back from the One Night in America sessions, and Michael Jerome on drums (Jerome also played with the Five Blind Boys of Alabama who, along with Ben Harper, guest on the set). Sanctuary opens with Harper's "Homeless Child," and the composer guests on his Weissenborn guitar, ramping it down and laying out the killer slide blues for Musselwhite to wrap and moan his lyrics around and into the void of the night sky. With a skeletal chorus provided by Harper and Sexton, the tune goes from the porch to the stratosphere with only the six-string razor and the vocalist's funky harmonica to frame its flight. Harper also guests on Musselwhite's amazing swamp autobiography with the Blind Boys. The song walks the knife's edge of the sacred and profane; it's a hymn of both acceptance and repentance. There is a wonderful tension here, between the darkness of the narrative and the exuberance of the backing vocals and the shuffling drum kit. The atmospheric edges in Musselwhite's mix, though, are better-evidenced by the tunes he plays with his own band, whether it be in the nasty, guttural blues of his own "My Road Lies in Darkness," or in the spooky, laid-back humidity of Randy Newman's "Let's Burn Down the Cornfield." With a cover of Chris Youlden's "Train to Nowhere" -- a song made popular by Youlden's band at the time, Savoy Brown -- the listener travels through time and space: Savoy Brown was trying hard to capture the feel and spirit of the Delta in their version, as the music of the region traveled north to Chicago. Musselwhite, with the Blind Boys, embrace the feeling and take it right back down the Mississippi River, thereby creating a double. While there are no weak moments on the set, a couple of the other standouts include the band's instrumental "Shadow People," which evokes the dread, mystery, and sexy darkness inherent in the music's grain; a stunningly edgy version of Townes Van Zandt's "Snake Song," and a sweet, low, rumbling, sexy twitch that comes from Eddie Harris' "Alicia." Sexton contributes his own magnificent "The Neighborhood" to this; in the deep, expressive world at the bottom of Musselwhite's voice it becomes a song that opens into the shadow side of the world we inhabit everyday. The album ends with a harp solo on "Route 19 (Attala County, MS)"; the player breathing it through the subtle body channels of marrow, bone, and heart cavity, into history, making an offering to the listener as a gift. Sanctuary sets a standard for authenticity, vision, and inspired excellence. Amen.