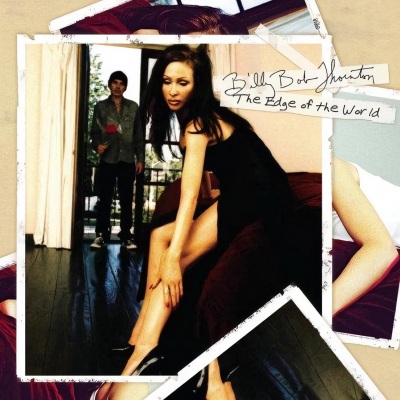

The Edge of the World

by Thom JurekOn Private Radio, his first album, Billy Bob Thornton and his co-collaborator Marty Stuart crafted a quirky, off-kilter series of haunting songs/stories that walked around country music like it was the middle of the night. The result was a poetic and moving recording filled with expressionistic images and characters who could have come from Sling Blade. Not so with Edge of the World. Thornton is less a poet here than a guy who wants to write and sing rock & roll songs. And he does it in spades. This is the real working-class hero album. There is no rebellious street corner poet here informing listeners of the hidden greater meaning in broken narratives of everyday life with elegant language and vulnerable hooks and melodies. Nope. This is a balls-out rock & roll record where Thornton takes off the gloves; it could have been recorded by the sheriff Darl, the character he plays in The Badge. In songs like "Emily," "Everybody Lies," and "Island Avenue," Thornton is the unredeemed side of Bruce Springsteen and John Mellencamp. Here's the guy who is trying to learn to write songs and gets to record them. He talks plenty of garbage, but it all feels true rather than, as in the case of the aforementioned songwriters, an archetype for truth. He's not interested in convincing the listener of anything. These songs are small truths, they reflect some picture Thornton has decided is worth etching into his psyche and coming up with a way of expressing: which is rollicking, freewheeling, full of a biker's hidden human charm and a reluctant, Monday through Friday garage mechanic's wild heart on a lonely Saturday night. On these sides, Thornton relies on his road band with the requisite appearances by special guests. The late Warren Zevon appears on "The Desperate One," the most poignant song on the record, where Thornton's voice spits his anger through a rambling, anthemic country-rock wall of noise that the Eagles tried many times to construct but could never let go enough to pull off. Daniel Lanois, Chely Wright, David Briggs, and Marty Stuart are also present in strategic places, such as on "Savior," where Lanois' trademark atmospheric approach to playing the steel guitar puts the message of the tune in the blood of the listener. The chunky organ playing of Zevon is a stark contrast to Lanois' guitars on "Midnight Train." On "To the End of Time," a broken and edgy love song near the end of the album, Mickey Raphael and Stuart turn in tough, bluesy performances to root the track in some obsessive bloodline of desire never extinguished. The only thing that doesn't work all the way here is the overly lush cover of Fred Neil's "Everybody's Talking," but even this -- with its organs, twanging Telecasters, and strings -- is compelling for its shambolic treatment. This record isn't a train wreck, but it is a messy living room on Sunday morning after a haphazard party the evening before. It feels real, dirty, overly ambitious, and necessary for anybody who enjoys the sound of rock & roll as a soundtrack to life rather than as an artistic concept.