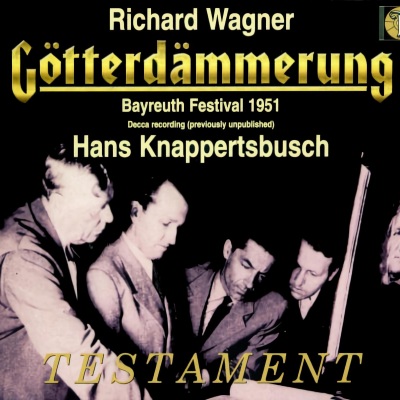

Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung (Bayreuth Festival 1951)

Brünnhilde - Astrid Varnay Siegfried - Bernd Aldenhoff Gunther - Hermann Uhde Waltraute - Elisabeth Höngen Alberich - Heinrich Pflanzl Hagen - Ludwig Weber Gutrune - Martha Mödl Woglinde - Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Wellgunde - Hanna Ludwig Floßhilde - Hertha Töpper Erste Norn - Ruth Siewert Zweite Norn - Ira Malaniuk Dritte Norn - Martha Mödl Chor & Orchester der Festspiele Bayreuth Chorus master/Chorleitung/Chef des choeurs: Wilhelm Pitz conducted by/Dirigent/direction: Hans Knappertsbusch Recorded/Aufgenommen/Enresgistré: Festspielhaus Bayreuth, Sunday/Sonntag/dimanche, 4 August/aout 1951 It's still easy to imagine the anticipation that must have attended the Bayreuth Festival in 1951 when it reopened for the first time since the war. This was the epoch-making summer when Wieland Wagner began to unveil a bold rethinking of his grandfather's canon--and to distance his art from the ideological trappings of the Third Reich--through increasingly austere and abstract productions. One member of the recording teams on hand (rivals EMI and Decca) was John Culshaw, who would later become famous as the mastermind producer behind the first and still most-popular studio recording of the Ring. Despite problems with the rest of the cycle, Culshaw managed to register its epic concluding work to his satisfaction. Yet that legendary Götterdämmerung sat in the archives for almost half a century due to contractual complications. This release at last makes its glories available. Conductor Hans Knappertsbusch--a master of the grand old tradition who is above all prized for his incomparable accounts of Parsifal--presides over a majestically scaled performance right from the doom-colored opening chord. Its cumulative power builds like a juggernaut. Though Knappertsbusch's famously weighty pacing makes this probably the slowest Götterdämmerung on record, the tempi rarely feel distended but rather enable Wagner's densely webbed, late-style ripeness to reverberate with its full emotional resonance. Knappertsbusch also knows how to keep a particular dramatic moment taut without losing his command of the larger context, as in the confrontation between Brünnhilde and Waltraute or Act II's vengeance trio. And in the funeral march you won't hear Soltian muscle but a profoundly resigned summation far subtler in its impact. The relatively young cast features some of Bayreuth's finest postwar artists, several making their festival debut during the 1951 reopening. Astrid Varnay proves her claim as Flagstad's successor, imbuing Brünnhilde's transfiguring love and subsequent betrayal with a presence that is completely gripping from the beginning to the cycle's cataclysmic end. Variety of color endows Bernd Aldenhoff's Siegfried with more dimensions than most interpreters; he can be sweet-voiced or imperious, rising to glory in the Act I duet and summoning a blustery bravado in his scene with the Rhinemaidens. Marth Mödl's angsty, dark-hued tone gives Gutrune an intensity far beyond the usual passive dimwit, while Hermann Uhde portrays her brother--despite his straining upper range--as a complex tangle of ambition and self-doubt. An integral part of this tremendously tight-knit ensemble is Ludwig Weber's intimidating Hagen. He gives the villain a truly Iago-like scope, brooding in the malignancy of his monologues and striking a chord of sheer terror in the scene of Siegfried's murder. In short, this set belongs in the collection of anyone interested in the performance of Wagner--or of great musical drama, period. --Thomas May