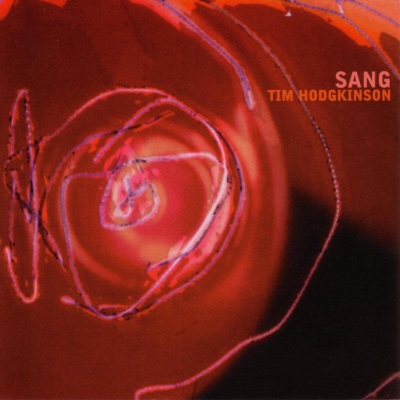

Sang

by Thom JurekHere are four Tim Hodgkinson pieces of varying length and style that are equally uncompromising and visionary. Hodgkinson works through all kinds of media (tape, film, processors, etc.) and, of course, musical instruments. The first track, "The Road to Ezrin," is for viola, piano, alto saxophone, two percussionists, and live electronic sound processing. Supposedly a tribute to the musicians of central Asia, this very spare, impressionistic work employs these instruments in cinematic ways, each a foreshadowing of what is to come: forest-like sounds where elemental influences in the shape of mode and color give way to eruptions of dissonant clusters on the piano and percussion. On "GUSHe," for B flat clarinet and tape, Hodgkinson whirls his way into the processed tape sound. This happens one whole tone at a time. The tape creates microtonalities as it engages the sparse language of the clarinet, which is reminiscent of Roscoe Mitchell's "S-II Examples." Both instruments engage in what is "gestured" playing, inviting one another into dialogue yet only accepting with another invitation. "The Crackle of Forests," for a "a large number of solo instruments and a mass of brass," is simply a rip off of the territory mined wonderfully by Frank Zappa years before in his incidental music, and Zappa got it from Boulez (though he interpreted it less seriously). This is musical masturbation at its very worst. It's not that there aren't any original ideas here that would be forgivable, it's that there aren't any ideas here at all -- despite his lengthy explanation of how the piece is supposed to work. If you can't hear it, it's not happening. Period. At over 22 minutes in length, it is insufferable. The last work, "M'A," is a montage of works for solo voice (provided by Frederico Santoro, a chamber orchestra work, and Hodgkinson's second string quartet. Here again, though all of these individual works may have merit in and of themselves in this dramatic context -- and it is that: full of color, dynamic and textural atmospherics -- they cannot sustain tension or interest for the nearly 20-minute duration of the piece. One gets the idea that Hodgkinson had been listening to a lot of Stockhausen's work from the 1960s when this work was patched together with the seams hanging out all over the place, but Stockhausen was careful to cover his tracks and allowed for the work to be new in places. Hodgkinson does no such thing; he seemingly just cuts and pastes here and there whenever a dynamic change is necessary. After seven or eight minutes, all the surprises are gone and what is left is merely academic noodling. Sang is a mixed bag to be sure, but the shorter works here are worth the time and effort to sort through the "artistic" excess.