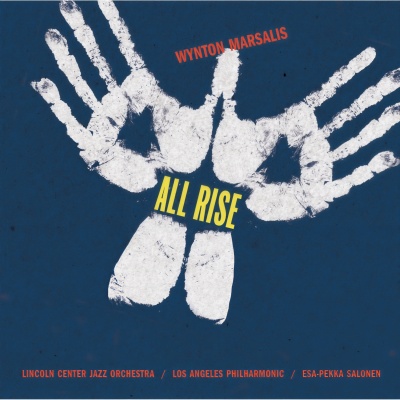

Marsalis: All Rise

Originally conceived for Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic in 1999 as a new millennium piece, this outlandishly scaled, exuberantly eclectic, 106-minute monster work for chorus, symphony orchestra, and jazz big band soon became known as a symbol of something completely different. Just two days prior to a scheduled performance by Marsalis, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl in 2001, the terrorists of September 11 struck — and the performance (and subsequent recording with these forces) became a memorial, almost a catharsis, to a terrifying event. Yet "All Rise" would have been a special work in Marsalis' output even without the historical context. Though not quite as lengthy as "Blood on the Fields," "All Rise" nevertheless is the most ambitious thing that Marsalis had written up to this time, a piece that brazenly tries to embrace the whole world (to cite Gustav Mahler's definition of a symphony) and succeeds better than one thought it might. It is also the most fascinating and enjoyable of Marsalis' concert pieces, where the listener shares the composer's delight in opening himself up to new sonic experiences that his highly debatable pronouncements on jazz have long ignored. Cast in 12 movements, the piece is supposed to have been built upon the example of the humble 12-bar blues, but actually, as in other Marsalis concert pieces like "Fields" and "Big Train," the primary driving force is Duke Ellington — and, to some extent, Charles Mingus. Yet Wynton also throws his classical experiences into the mix, including neo-classical Stravinsky and neo-Baroque brass. He even attempts a string fugue in "Movement 4"; it's stillborn, running in place, but you end up admiring his moxie and his deflating wit in the movement's subtext ("We discover we can do wonderful things, get the big head, and get lost in a labyrinth of our own magnificence"). He mines Cuban and Argentinean rhythms, he includes gospel strains, and he doesn't forget to include stretches of the straightforward neo-bop style that brought him to the world's attention in the first place. He is also very generous with the solos, handing them out to his colleagues in the LCJO while taking one extended coruscating turn himself in "Movement 5." Ultimately, the resonances between this work and September 11 are uncanny. In "Movement 5," following a sequence of war-like drumming, the chorus screams and sings the words, "Save us, O Lord" — which hit painfully close to home to the Bowl audience. And in the end, the sudden coda — played in Marsalis' most joyous Dixieland manner — was a release, like the close of a wake. Even if you have resisted Marsalis' more pretentious concert music in the past, this two-CD set may well make you a believer. ~ Richard S. Ginell, Rovi