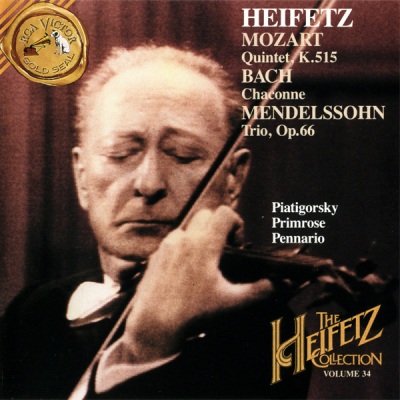

The Heifetz Collection, Volume 34 - Mozart, Bach, Mendelssohn

The three masterpieces on this CD make a pleasing enough program but have little in common. It takes, therefore, a bit of ingenuity—in this time of thematic programming—to find a unifying factor among them. One possibility would be to point out that Heifetz, who had a lifelong devotion to chamber music, recorded all three works in the Indian Summer years of his legendary career—the Mendelssohn in 1963 and the Mozart in 1964, both products of the Heifetz-Piatigorsky Concerts series of recordings; and the Bach in 1970 for his television special. Another possibilty might be to observe that Bach enormously influenced both Mozart and Mendelssohn. But the point most worth making, perhaps, is that each of these particular compositions was, itself, influential in shaping that coursing river known as Western Classical Music. Bach's mighty Chaconne is indisputably one of the seminal examples of its genre. Composed at Cöthen in 1720 as the finale of the Partita No. 2 in D Minor for unaccompanied violin, this magnificent synthesis of architectonic mastery and heartfelt emotion has often been performed on its own, and it has been heard in many fascinatingly diverse transcriptions for instruments other than violin (one can learn a great deal by comparing the austere Brahms piano arrangement for the left hand alone with Busoni's far more licentious two-handed one, also for piano). The chaconne, particularly as Bach enriches it, gives us variation form at its most compact: in place of dwelling upon and characterizing each variation, his work moves powerfully toward its various phases and goals by way of groups, building to an initial climax, then passing into a maggiore section and finally returning to the original D minor for an introspective and ruminative summing up. Beethoven's 32 Variations in C Minor for piano and the finale of the Brahms Fourth Symphony are but two examples of later masterworks that followed in the Chaconne's giant footsteps. Stride and footsteps again come to mind in the expansive opening Allegro movement of Mozart's Quintet in C, K.515, completed in 1787. From its first vamping measures, one hears a kind of locomotion that is encountered again in the first movements of Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony and the first "Razumovsky" Quartet, both obviously patterned after Mozart's prototype. When Heifetz and his colleagues recorded the quintet in 1964, a new edition of it had just been published by Bärenreiter. One of the controversies raised by the new text was where the Menuetto should appear—it had customarily been played before the Andante, but Bärenreiter's scholarly editors decided that it should come after. The Heifetz ensemble followed Bärenreiter's directive, but one of the advantages of the compact disc is that—with the mere push of a button—the home listener can program it either way. The C Major Quintet is analogous to Mozart's "Jupiter" Symphony in that it is large-scaled and heroic in concept. Indeed, the finale—a sonata/rondo—is the longest movement in terms of total number of measures in Mozart's non-sym-phonic instrumental music. Like Bach and Mozart, Mendelssohn grew up in a musically cultured household and came to chamber music at an early age: surviving from his adolescence are a set of charming piano quartets, a sextet (also with piano), the superlative Octet for strings and, of course, the wonderfully poignant string quartets, Opp. 12 and 13. His two published trios, in D minor and C minor, respectively, are not from that formative period but from the peak of his maturity. Although both are in four movements, each has its own aesthetic profile. The C Minor Trio is somewhat darker and tougher in character, with a less accessible persona. It dates from 1845, the year in which Mendelssohn also composed his six organ sonatas and the Op.67 volume of Songs Without Words. The Trio's opening movement, in sonata form, presents the dichotomy of a typically dramatic first theme and a songful contrasting idea. The Andante espressivo second movement is an idyllic affair in swaying 9/8 meter, tinged with a strain of Victorian sentimentality. A lively scherzo follows. But, for many, the finale is the most noteworthy movement. Mendelssohn revered Bach and, in fact, worked mightily to restore his great predecessor's music to active performance. Little wonder, then, that some have drawn an analogy between the leap of a ninth in the opening theme of this movement and the Gigue of Bach's English Suite in G Minor. And for the movement's second theme, there is a suggestion of Chopin's Op.39 Scherzo, composed about six years before this trio. But if Mendelssohn "borrowed," he also, in this instance, influenced the young Brahms, who quoted, almost verbatim, the opening theme of this finale in the third movement of his F Minor Piano Sonata. —Harris Goldsmith