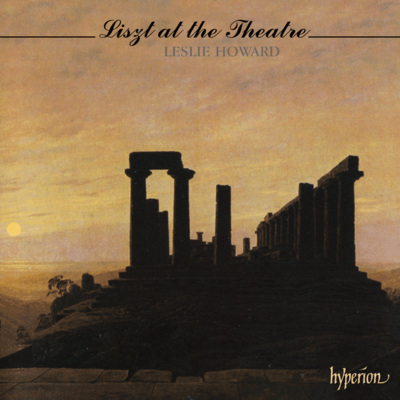

Liszt: The Complete Music for Solo Piano, Vol.18 - Liszt at the Theatre

The Temple of Juno at Agrigentum (c1830) by Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) CDA66575 Recording details: April 1992 St Martin's Church, East Woodhay, Berkshire, United Kingdom Produced by Tryggvi Tryggvason Engineered by Tryggvi Tryggvason Release date: June 1992 DISCID: 7D12510B Total duration: 77 minutes 34 seconds 'Another superbly produced instalment of this awesome endeavour. Enthusiastically recommended' (Fanfare, USA) 'Scintillating ... Fine recording. Not to be missed' (Classic CD) 'Nothing but praise for the way he meets so many superhuman technical demands' (Gramophone) Whilst Liszt’s piano music derived from music for plays is a much smaller body of work than his catalogue of operatic pieces, the approach in his methods of composition, elaboration and transcription remains broadly the same. As far as present Liszt scholarship permits one ever to be categorical, this recording contains all of Liszt’s works in this genre. The quite extensive scores for the theatre commonly written in the nineteenth century eventually overpowered both the plays they accompanied and the time limit for an audience’s concentration. Today few would relish an uncut performance of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt given with the entire Grieg score if they knew beforehand that the evening would take at least one hour longer than Götterdämmerung, and it has been only rarely that Mendelssohn’s Shakespearean efforts have been produced in tandem with the complete play. But much incidental music—which can take the form of overture, dances, songs, intermezzos or entr’actes, choruses or melodramas, as well as shorter flourishes and fanfares, entrance and exit fragments—has always had an independent life in the concert hall, and for Liszt, to whom the propagation of all kinds of music was a sacred duty, selected several works for re-working as recital pieces. For some reason the piano transcription of the ever-popular Turkish March from The Ruins of Athens disappeared from view, to be replaced in pianists’ affections by the well-known transcription by Anton Rubinstein. Liszt’s version—every bit as interesting—is one of his rarest works. The identical pages stand at the head of the score of Capriccio alla turca, a much more extensive piece in Liszt’s virtuoso manner, in which the March (No 4 in Beethoven’s score) is succeeded by the Dervishes’ Chorus (No 3 in Beethoven’s score; also, at one time, known in a piano transcription by Saint-Saëns) in a section marked Andante fantastico, full of diabolical trills. Eventually the March returns, much transformed, and both themes are used to produce a triumphant coda. Possibly because of its difficulty, the Capriccio gave way to Liszt’s last work on the same material, the Fantasie, which started life as a work for piano and orchestra but which was substantially revised and reissued together with versions for solo piano, piano duet, and two pianos. The Fantasie begins with a transcription of the orchestral part of the March and Chorus (which form Beethoven’s No 6, and which Beethoven reissued as opus 124 with minor changes for the music to Die Weihe des Hauses—‘The Consecration of the House’) which breaks out with a cadenza in octaves into a much more fantastic working of the material, which then subsides into the Dervishes’ Chorus. From this point, there are many resemblances to the Capriccio but the atmosphere is rather more controlled and the fireworks held in abeyance until the coda. There, closing passages of the March and Chorus lead into a final peroration upon the other two themes. Liszt’s own contribution to the literature of incidental music comprises just two works—Vor hundert Jahren, which is an overture-cum-melodrama for spoken voice and orchestra for a play by Halm (S347, unpublished to date), and an overture and choruses to Herder’s play Prometheus Bound, which was among those works too large to be accommodated on the same evening as the play for which it was intended. In the end, Liszt revised the Prometheus work thoroughly, transforming the overture into what we now know as the independent symphonic poem Prometheus. The symphonic poem could still serve as an overture to the choruses, which were now punctuated with a poetic oration by Richard Pohl to get through the gist of Herder’s play in indecent haste to allow room for well over an hour of music. Amongst the choral sections of the work, the Reapers’ Chorus proved instantly popular and Liszt issued versions of it for piano solo and for piano duet. Among an output so vast as Liszt’s it is perhaps an inevitable pity that this attractive trifle has fallen into oblivion. Quite why Liszt described Weber’s music to Preciosa as an opera must remain a mystery—indeed, the shape of the piece is not greatly different from Liszt’s Prometheus Choruses—but we can only thank him for bringing this charming aria to our attention. At one time, Liszt’s often witty interpretation of the famed Mendelssohn Wedding March was a regular recital war-horse. It could be that familiarity with Mendelssohn’s original—not to mention innumerable versions of bits of it encountered in so many parish churches and Hollywood films—has stifled interest. But the idea of performing this work, along with Liszt’s fiendish arrangement of the Introduction to Act III and Bridal March from Lohengrin at a marriage ceremony remains a Schwarzenplan of the present writer. Liszt furnishes Mendelssohn’s work with a ghostly, almost satirical introduction, and then a rather light-hearted version of the main material before he gets to the piece proper. Then the main section is subject to variation whenever it reappears. Mendelssohn’s first interlude is faithfully transcribed, but the F major section with its flowing theme ends up flowing into very strange harmonic waters in order to prepare for the interpolation of the Dance of the Elves. Liszt is loth to let go the elvish music, so he allows it to permeate the return of the march before the triumphant coda is given a triumphalist transcription. Liszt’s elaborations of three works by Eduard Lassen call for some special comment. Lassen (1830–1904) succeeded Liszt as Kapellmeister at the Weimar court in 1858, and held the post until 1895. As well as the works presented here, Liszt made transcriptions of two of Lassens’s songs. Lassen, who was an ardent Lisztophile and Wagnerite (as one can instantly tell from his music) was responsible for several of the chamber-music versions of Liszt’s later works which have come down to us as Liszt’s own because he used Lassen’s version as the basis for his own revisions. Now sadly relegated to one of the footnotes to the history of music, Lassen is almost unrepresented in print or on record except in Liszt’s transcriptions. As the title suggests, the Symphonic Intermezzo is a large-scale orchestral work. Its long-flowing melodies are constructed from smaller cells, and Liszt sometimes sequentially extends the material in the way characteristic of his later works. The proud opening music leads to an Andante amoroso and an absolutely splendid and memorable melody which is worked out at some length. The final section of the work, Feierlich ruhig (‘Proudly peaceful’), opens with a series of chords and arpeggios which recall the prelude to Parsifal, and this passage occurs four times in different keys, alternating with fragments of the Andante and rounded off with a bell-like coda that refers to the opening as well as to the bell-motif from Parsifal. Liszt used the fifth and eighth numbers of the eleven pieces in Lassen’s music to Hebbel’s drama Nibelungen, which has some story-line in common with Wagner’s ‘Ring’. In both cases, Liszt extends the original material. Kriemhild, somewhat transformed into Gutrune in Wagner, is memorable in the Nibelungenlied for despatching the villain Hagen after the death of her husband Siegfried. Bechlarn (Pöchlarn in the Nibelungenlied) is the location where the noble minstrel Volker sings a public serenade of tribute to Gotelind. Lassen’s Serenade, in Liszt’s hands, is of a touching and naive simplicity. Goethe’s masterpiece has attracted a great many composers, and Lassen’s contribution is a substantial one. His Faust score has some sixty-four numbers to it. The ‘Easter Hymn’ (Lassen’s Part 1, No 2), the hearing of which interrupts Faust’s resolve to kill himself, is straightforwardly transcribed, but the Hoffest (‘Court Celebration’) is Liszt’s own combination of two numbers (2 and 3) from Part Two of Lassen’s work. Here Liszt greatly varies and elaborates Lassen’s themes in an introductory march and a very gallant and ornamental Polonaise. Leslie Howard © 1992 Works on This Recording 1. Capriccio alla turca from Beethoven's "Die Ruinen von Athen", S 388 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1846; Hungary 2. March from Beethoven's "Die Ruinen von Athen", S 388a by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1846; Hungary 3. Fantasie on Beethoven's "Ruinen von Athen", S 389 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1865; Rome, Italy 4. Wedding March and Dance of the Elves from Mendelssohn's "A Midsummernight's Dream", S 410 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1849-1850; Weimar, Germany 5. Einsam bin ich from Weber's "La preciosa", S 453 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1848; Weimar, Germany 6. Interlude to Lassen's "Über allen Zauber Liebe," S 497 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: ?1882-83; Rome, Italy 7. Pastorale from Beethoven's "Prometheus Bound", S 508 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: 1861; Hungary 8. Aus der Musik zu Hebbels Nibelungen und Goethes Faust [after Lassen], S 496 by Franz Liszt ■ Performer: Leslie Howard (Piano) ■ Period: Romantic ■ Written: Weimar, Germany ■ Notes: Composition written: Weimar, Germany (1878 - 1879).