Schubert: Hyperion Song Edition 35 – Schubert 1822-1825

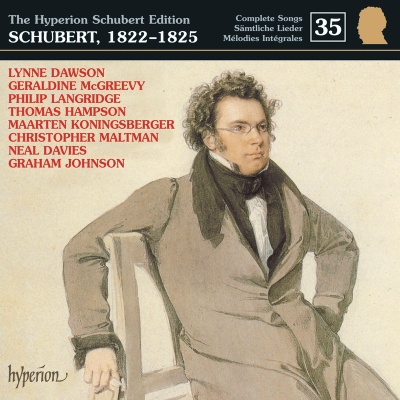

Recording details: January 1998 St Paul's Church, New Southgate, London, United Kingdom Produced by Mark Brown Engineered by Antony Howell & Julian Millard This volume of our Schubert Edition is devoted to songs written in the last years of the composer’s life and contains some of his greatest, though not necessarily best-known Lieder. The two immortal songs in this volume, universally known and loved, are Lachen und Weinen and Du bist die Ruh, from 1822 and 1823 respectively. But other masterpiece are here too—Schwestergruss, Dass die hier gewesen, and Totengräbers Heimwehe—as well as a clutch of rare songs and partsongs. Again we have a stellar line-up of singers including Philip Langridge and Christopher Maltman. During the period encompassed by Volume 35, and in contrast to the fecundity of the earlier years, a comparatively small number of songs were composed. On the other hand, each of these songs is, almost without exception, of especial beauty and significance. The majority of them have already been issued in the series – not only Die schöne Müllerin itself, but also four of the seven Lady of the Lake songs (Volume 13), the Matthäus von Collin songs (Volumes 3 and 5), the Craigher settings sung by Margaret Price (Volume 15), the Schulze settings performed by Peter Schreier (Volume 18), and so on. However, the songs that remain to be issued from this four-year period are far from negligible. If Volume 35 contains a few performances sung by distinguished artists some years ago, the majority of the disc comprises important songs recorded recently. A glance at the list of lieder on this disc will reassure the listener of the quality of the music; of its pedigree, it is enough to say that Schubert wrote it in his middle to late twenties. At the heart of the programme are five of the Rückert settings of 1823, four of which are uncontested masterpieces. Two fine settings of Bruchmann, and two of Mayrhofer, show the composer’s continuing enthusiasm for poetic inspiration close to home; and the last Craigher setting, Totengräbers Heimwehe, a song which has always been a favourite among male singers, shows Schubert at the height of his powers. There are, in addition, lesser-known choral settings of Christian Ewald von Kleist, de la Motte Fouqué and Walter Scott which may mostly be ranked as first-class Schubert. One would expect nothing less from the composer in the full flower of his maturity. The high quality of the composer’s musical output is something of a miracle considering that the years in question contained the most unpleasant and tortured moments of Schubert’s short life. Of course, the optimism inherent in human nature is such that even the sword of Damocles seems sometimes to shift from directly over the sufferer’s head. Interspersed with much unhappiness and serious illness were moments of compensatory joy and relaxation; indeed, this period contains the greatest range of highs and lows which Schubert was to experience in his 31 years. These opposing poles of experience might be exemplified by the sick composer’s undoubted desperation in hospital in the autumn of 1823, and his elation during the most exciting holiday of his life, a journey through Upper Austria in the summer of 1825. The opening quartet on this disc is Gott in der Natur. This was composed in the late summer of 1822, during the period that the composer was working on his Mass in A flat, D768. At more or less the same time, Schubert had embarked on the Symphony in B minor, D759, which we know as ‘The Unfinished’. Other contemporary works include the Quartettsatz, and the ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy. Although the first half of 1822 had been disappointing in many ways (chiefly for the failure of Alfonso und Estrella to reach the stage, and a falling-out with the singer Vogl which was also connected to this project), the misfortunes of the period, mainly linked to finances and thwarted ambition, were as nothing in comparison with the health crisis which followed at the end of the year. Sometime in the last months of 1822 the composer was diagnosed as suffering from syphilis. We are tempted to imagine that the song Schwestergruss, with its reference to the pleasures of the flesh (the poet Bruchmann uses the religious metaphor of ‘der Erdengott’ to embody such temptations, and the phrase ‘der grause Tod’ – fearful death – to describe the consequences), might have seemed uncomfortably apposite to the composer at the time. In this poem, the ghost of Bruchmann’s sister warns of an afterlife in hell; Schubert’s purgatory, however, was in the present. That such marvellously radiant Goethe songs as An die Entfernte, Am Flusse, Wilkommen und Abschied, were composed in December 1822 is a sign that creative inspiration can flow at the worst of times. But in this context, the fervent plea at the end of Der Musensohn that the poet (and thus the composer) should be allowed to find rest and comfort on the breast of the beloved, gives one pause for thought. At this stage of Schubert’s life, very little of his output can be written off as superficial or simple; even the merriest happy-go-lucky song somehow contains tender emotion and hidden tears. The documentary biography for the opening of 1823 is silent until the end of February concerning this catastrophe. The surviving Schubert documents in general tell us little enough, and seldom about the composer’s thoughts and emotions. This tendency to discretion in committing to paper matters of a passionate and private nature came from living in a state where the less that was known of one’s affairs by the snooping police the better. And living in a small town like Vienna, with friends close at hand, there was often no need to write things down. So there is no letter in which the composer gives vent to an anguished cry of surprise and fear at the discovery of the symptoms which would change his life forever; we have to wait until much later (the end of March 1824) when Schubert poured out his feelings in a letter to his friend Kupelwieser in Rome. Mention of the illness, in guarded and cryptic terms, seeps slowly into the bloodstream of the biography. After the initial shock there are a few correspondents, normally writing among themselves and not directly to Schubert, who refer to the state of the patient’s health without naming the malady. We must surmise that it was the discovery of his illness which made the composer leave the Schobers where he had been a guest, and to return to the paternal home, the schoolhouse in the Rossau. (We know from Schober’s disinclination to visit the composer in his last days in 1828 that he disliked the sickroom and could never have played the nurse.) What reception awaited Schubert at home in these sad circumstances, and whether he was able to share the details of his affliction, we shall never know. His stepmother and his brother Ferdinand were always kind and supportive; his sternly religious father much less so. On the whole, one has the impression that most of the composer’s friends rallied round as best as they could, and mostly rather better than Schober who, in any case, soon decided to move to Breslau in pursuit of a career in the theatre. There are no personal letters written to the composer in commiseration at this time, but Franz von Bruchmann’s text for Der zürnende Barde, set by Schubert in February 1823, is about a defiant bard fighting back against adversity; manly determination and rage are surely better than apathy when it comes to surmounting the cruel twists of fate. In any case, the shattering of Schubert’s lyre must have seemed unthinkable to those who knew and loved him. And fight back Schubert did, although it took him quite some time (until he composed Die schöne Müllerin in my opinion) before he regained his equilibrium. Bruchmann later referred to the fact that the winter of 1822/23 ‘brought with it a brilliant life enhanced by music and poetry [which] quite bewitched me’. So, despite all, the social life of the circle, much enhanced by Schubert’s music, continued apace. Indeed, at this stage, it had a momentum which did not rely on the composer’s presence. Schubert’s absence was often written off as absent-mindedness, or simply because he was known to be hard at work. Gossip was no doubt rife within a small circle concerning the cause of his illness, but it would have been in the nature of his closer friends to hide the truth from the curiosity of outsiders. Later in the year, Karl, Beethoven’s nephew, noted in the great man’s conversation book: ‘They greatly praise Schubert, but it is said he hides himself’. Only at the end of February 1823, in a letter to the court official Ignaz, Edler von Mosel concerning the future of Alfonso und Estrella (there was none, sadly), does Schubert mention being confined to his house because of illness. Apart from this (and the letter might just as well refer to a minor indisposition as anything more serious) a reading of the documentary biography might suggest that life was going on as normal. We find a flowery poem written by Schober in honour of the New Year, and Schubert’s secretary and factotum Josef Hüttenbrenner submits accounts for 1822 (with wrong totals caused by errors of arithmetic rather than dishonesty), but there is little else, and it is this silence which is most eloquent. These opening months of the year must have been hell for the composer. He was grappling with all the harrowing issues arising out of his illness. It was now out of the question for him to think of himself as a prospective lover for fear of infecting others. Even if a side of him wanted to believe in a ‘cure’, and he was to work assiduously towards that end with various doctors (whose help, however well meant, amounted to little more than quackery), the long-term prognosis was a grim one. On some days he obviously felt better than others. In his case it seems that the painless primary stage of the disease was rather quickly followed by secondary symptoms which made him feel unwell in various ways, on and off, for the next two years. Nevertheless composition somehow continued. The Piano Sonata in A minor, D784, was written in February and strikes a disturbing note of melancholy. The work was being written just as the ‘Wanderer’ Fantasy appeared in print, but it was so darkly introspective that it was rejected by Diabelli for publication. Money was a continuing problem and Schubert, never adept at business matters, seems to have needed a lump sum badly – perhaps connected with what he feared would be a potentially expensive medical emergency. As a result, he sold the rights of his Opp 1 to 7, and later Opp 12 to 14, to Cappi and Diabelli who until then had been selling his songs on a commission basis. Thus, in a stroke, he threw away the clever business initiative that had been planned by Ignaz von Sonnleithner as a means of rescuing him from debt. If the composer had been more patient, and if he had held on to his copyright, burgeoning sales of his lieder would have ensured much better earnings. One cannot altogether blame Diabelli for looking after his own business interests, but Schubert was convinced that cheating was afoot, and the break from Diabelli which almost inevitably ensued (in April 1823) occasioned an extremely cutting missive from Schubert containing a new and acrimonious tone which we seldom find in his letters. One can sense the personal stress behind this letter, a sense of outrage that with everything else crumbling in his life he should also have to worry about being cheated by a publisher. He now embarked on a new relationship with the firm of Sauer & Liedesdorf. The composer’s talents were also becoming appreciated outside Vienna: in 1823 he was made an honorary member of the Styrian Music Society in Graz, and received a similar honour from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Linz. In the meantime, the most extended composition of this period for voice and piano is a setting of the poetry of his beloved, if self-centred and unreliable, friend Franz von Schober. In the great vocal rondo Viola we can once again look behind the meaning of the poem and its flower allegory to find a tale of abandonment and death in which one can find many echoes of Schubert’s own situation. It is just possible that Schober wrote the poem about the poor withered snowdrop with his blighted friend Schubert in mind, but it seems more likely that the composer lavished such great music on a relatively banal poem as a result of heightened compassion for those, like him, who were cut off in their prime. The other Schober flower ballad, Vergissmeinnicht, composed in the following month, does not seem to have engaged him in quite the same manner. Other choices of song text in the spring of 1823 also seem significant – Schiller’s visionary Der Pilgrim, for example, is a song which fights back in the spirit of Der zürnende Barde. There is also a rather little-known song, the poem of which was possibly written in response to the composer’s tragedy: Schober’s Pilgerweise suggests that the symbolic pathos of Schubert’s unfortunate personal predicament had already struck his contemporaries as a subject fit for poetry. And even if the similar plight of pilgrim and composer was a coincidence where life imitates art, Schubert must have found horribly apposite the image of an artist going from house to house, needy of love, and blessing the world with his music as his own happiness is torn asunder. Certainly, the composer himself was moved to write verse at this time, a sign of inner crisis throughout his short life. In the poem Mein Gebet (May 1823) he bewails his fate as a sad pilgrim: ‘Behold, as nothing in dust I lie / A prey to grief unknown to all / My life a pilgrimage of pain (‘meines Lebens Martergang’) / Now nears its everlasting end.’ In all the songs of this period it is as if the visionary quality in his nature has come into even sharper focus; it has, of course, always been there, but in an 1823 song like Auf dem Wasser zu singen, which seems at first to be gently descriptive and entertaining, quickly reveals a more exalted note, a touch of the sublime. In this music, poised between A flat major and A flat minor, ecstatic reaction to the beauties of nature leads to intimations of mortality. The ‘Ach’ at the beginning of the last verse (‘Ach es entschwindet mit tauigem Flügel / Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit’) seemed to encapsulate the whole sad realisation of the swift passing of time, and the inevitable farewell facing us all. Certainly the poem owes much to Goethe’s Gesang der Geister über den Wassern which holds out the possibility that the soul of man will not perish, that it will somehow be recycled as part of nature’s grand plan, just as the waters of the stream turn into mist, cloud and rain, and thence return to the river. In the absence of a religious philosophy Schubert must have thought hard about immortality, almost certainly not aware that it was already his. In some works of this period we hear the gentle surrender of hope, in others the fervent, and pathetically hopeful, ecstasy of the swan-song. Here is a man coming to terms with living and dying, no longer as part of a poetic hypothesis, but as a result of real fear and mortal danger. A similar sense of leave-taking pervades the great single-page Collin setting Wehmut. Here is one of Schubert’s most eloquent warnings that nature’s beauty will vanish with our demise, and it comes to us heightened by the composer’s painful awareness of the truth of Collin’s words. All three of the Collin songs of 1823 are masterpieces: apart from Wehmut there is the dark and obsessive Der Zwerg which is the apotheosis of the Gothic ballad reduced to pithy proportions and spine-tingling directness. As if to corroborate that Der Zwerg pre-shadows the world of Freud and psychoanalysis, the immortal Nacht und Träume dates from June 1823. That these poems exactly suited Schubert’s mood of the time is beyond doubt; their mood is far from the composer’s previous collaborations with that poet – the duet Licht und Liebe, and the musical letter Herrn Josef von Spaun. Schubert’s return to the poetry of Collin may have something to do with the fact that the circumstances of his illness had led to a friendship with a Dr Bernhard who was the poet’s brother-in-law. One must not get the impression, however, that Schubert retreated solely into a world of lied composition. Concern about his finances seems to have made him redouble his attempts to make something of himself in the theatre. Thus in April 1823 he finished a one-act opera based loosely on Aristophanes’ Lysistrata which had the title of Die Verschworenen (D787). Austrian censorship regulations, sensitive to the idea of oath-taking and potentially seditious societies, made it necessary to re-title the work Der häusliche Krieg. This is a delightfully tuneful and witty piece (still a producer’s first choice of the Schubert’s operas when something compact and easily stageworthy is needed), but it was never performed in the composer’s lifetime. In May Schubert embarked on something much more ambitious: the opera Fierabras written in collaboration with Josef Kupelwieser, brother of the artist Leopold. There is no doubt that Fierabras contains some of Schubert’s most beautiful music for the theatre, but it was bedevilled on two counts: the dramaturgical flaws and lack of flow that made this composer’s theatrical works seem leaden and unwieldy on stage, and the conditions in Vienna at the time which were increasingly hostile to German opera in the face of the public’s hunger for the imported article from Italy. The late John Reed avers that Schubert spent some time in hospital in June 1823. Most other modern commentators date this as having happened some months later. The summer offered some respite from Vienna, and above all from what were probably strained conditions at home in the schoolhouse. For neither the first nor last time the singer Johann Michael Vogl took the composer under his wing and arranged for a recuperative holiday in Steyr and Linz which lasted from mid-July to the end of September. Schubert and Vogl now seemed to have been reconciled after a period of awkwardness in 1821/22, and visits from Spaun and Mayrhofer, both natives of the region, were also part of the holiday agenda. One can imagine this break being organised as the result of a war council of friends with the theme ‘something must be done to help poor Schubert’. Much music-making took place, and the composer was well enough to accompany Vogl at the piano on a number of occasions. The song Greisengesang was one of the works that Vogl performed at the monastery of St Florian with the composer. Even in this restful atmosphere (‘Here I live very simply,’ he wrote from Steyr in August, ‘go for walks regularly, work much at my opera and read Walter Scott’) Schubert suffered relapses where he felt very unwell for periods. Indeed, he confesses in a letter to Schober that he doubts whether he would ever recover. These bouts of illness seem to have taken various forms, all of them fitting the medical picture of secondary syphilis – headaches, sore limbs and pains in the bones, as well as an inflammation of the larynx which made Schubert, normally an unabashed performer of his own songs, unable to sing. A loss of hair may have also been a direct result of the illness, although this could also have been caused by the ingestion of mercury as a treatment. In Schubert’s letter to Schober, the line ‘I correspond busily with Schäffer’ refers to August von Schäffer, a specialist in venereal illness with whom the composer kept constantly in touch. As already mentioned, there was later a Dr Bernhard who had a love of music and who fancied himself as an opera librettist. He was constantly in the composer’s company for a while, and seems to have been a know-it-all who was not popular with some of the Schubertians. Recent research by Michael Lorenz has ascertained that Bernhard (whose first name was Heinrich) was not a medical doctor, as has always been supposed, and that he could not have been the father-in-law of Matthäus Collin, as Deutsch avers. Collin’s father-in-law was Johann Bernhard (d1818) and Heinrich was his son. Thus Schubert’s Bernhard was, in fact, the poet’s brother in law. Despite Lorenz’s admirable research, Bernhard remains one of the most enigmatic figures in Schubert’s life. He was a gifted and opinionated bachelor who suffered from depression, and who suddenly disappeared from the circle in 1824. Whatever his qualifications, Schubert’s friends seem to have been certain that his proximity to Schubert was for medical reasons. Elizabeth McKay believes that Josef von Spaun, Schubert’s oldest friend and related to the Collin family, may have asked Bernhard to keep an eye on Schubert. Plagued himself with illness all his life, Bernhard may have had all sorts of theories regarding health and recuperation; indeed, he may have set himself up as an expert in this regard. In the absence of a real cure for syphilis, all sorts of ideas were vaunted, the holistic medicine of the time, concerning the patient’s diet and lifestyle. That Schubert was addicted to pipe-smoking is evident from a number of pictures and many comments; he was also overweight, and drank alcohol regularly, sometimes heavily. Elizabeth McKay also points out that it is very likely that the composer and his friends smoked opium (perfectly legally, in the form of laudanum) during their gatherings at the Wasserburg café. When he placed himself in the hands of medical gurus in the next two years, much of this was to change. Schubert went on various fasts, diets and purges which while not curing his infection had a fairly happy effect on his fitness, well-being and productivity. Even if Schubert had never caught a life-threatening disease, his lifestyle, weight, lack of exercise and addiction to nicotine would have made him a primary candidate for an early heart attack or stroke. On Schubert’s return to Vienna in the autumn of 1823 he moved into an apartment in the Stubentorbastei which was leased by his friend Josef Huber who was mercilessly teased for his height and ungainly behaviour. Huber was nevertheless a compassionate man, and Schubert was lucky to find shelter with him; it was out of the question to return to the schoolhouse in the Rossau as his stepmother was soon to give birth to her third child, Andreas Theodor. After some weeks Schubert’s condition worsened and it became obvious that he needed more professional nursing care than Huber was able to provide. It was probably in late September that he was admitted to the Allgemeines Krankenhaus, the general hospital in the Alserstrasse. It was likely that there he underwent ‘die grosse Kur’, an appalling regime where the patient, forbidden to wash, had to remain for long periods in mercury steam baths with side-effects almost as unpleasant as the original sickness. Thus it was that in a syphilitics’ ward, no doubt surrounded by more advanced cases of the same illness, a gruesome reminder of what may have been in store for his own future, Schubert wrote Die schöne Müllerin. The reader is referred to the booklet accompanying Volume 25 of this series for a discussion of this great work, and its importance in the development of this composer’s lieder-writing style. Schubert had never before set the poetry of Wilhelm Müller, and the result of this collaboration was a new type of music of powerful simplicity, sophisticated yet disarmingly direct. The strophic song-form, already honed and refined during 1816, was raised to a higher power than ever before, both in terms of the individual pieces and in the context of a compelling, integrated narrative. At the same time, the theme of blighted innocence, and the betrayal of an ardent young man’s fairest hopes, is surely closely connected to the composer’s struggle to reconcile himself to his new life. This was without long-term prospects perhaps, but in compensation Schubert now seemed able to make music on a sustained and exalted level which was scarcely matched by anything in the past. The laying of the miller-boy to rest in the millstream seems to have been of enormously psychological importance to someone who might himself have ‘gone under’ had he not discovered a new inner strength. Much of Schubert’s own desperation when confronted with the travails of his illness seem to have been transferred on to the shoulders of his suicidal young hero. In the earlier poem Mein Gebet Schubert wrote of a hoped-for resolution and purification: ‘Cast me into Lethe’s depths / And then, O Lord, allow new life / To thrive in purity and strength’. There were to be further outbreaks of illness and bitter unhappiness in 1824, but we sense that the worst moment of crisis in Schubert’s life had already passed. The low point of 1823 must have been his stay in that hospital with its Lethean mercury baths; but with the help of manuscript paper, ink and the poetry of Wilhelm Müller, he survived the experience. Schubert emerged from hospital in time to hear Weber’s opera Euryanthe on 25 October. He was not impressed by it, and neither was the Viennese public. The failure of the work made it inevitable that the completed Fierabras should be rejected by Domenico Barbaja, the Italian manager of the Kärntnertor theatre. Still Schubert longed for success in the theatre, and he seemed to be prepared to clutch at straws. In the autumn of 1823 he was persuaded to provide the incidental music for Rosamunde, a play by Helmina von Chézy, the librettist of the very opera, Euryanthe, which Schubert had not admired, and whose contribution to Weber’s work had played a considerable part in its failure. Allowing himself to be drawn into an association with von Chézy seems typical of Schubert’s lack of ‘savvy’ when it came to his theatrical dealings. The incidental music to Rosamunde has survived (unlike the play itself). The beautiful Romanze is a song that one hears on the concert platform from time to time in its piano-accompanied version, but the play, a farrago of complicated and sentimental nonsense, ran for two performances at the end of 1823 before disappearing forever. If one were tempted to comment on a terrible losing streak at this point of Schubert’s life, a glance at the song output re-classifies him as a secret winner. It was probably mainly in the autumn of the year that Schubert set a sequence of songs by yet another poet who was a relatively recent discovery. Friedrich Rückert’s Östliche Rosen had been published in 1822, and it seems that Schubert made a setting of Sei mir gegrüsst as soon as a copy of this book fell into his hands; five others were to follow in 1823. Here there is an oriental flavour reminiscent of Goethe’s West-Östlicher Divan. Schubert’s settings of those poems, a late flowering of Goethe’s genius, date mainly from 1821, but Rückert is a more modern and younger poet, and Schubert was still in the mood for new collaborations. Indeed he seemed to have sought them out. (His first encounter with the Styrian poet Karl von Leitner had produced Drang in der Ferne in 1823, and would result in more songs in 1827.) There was more than a touch of the exotic about the Moorish-inspired Fierabras, and the Rückert songs find the composer in the same mood for characterisation. There is nothing overtly ‘eastern’ about these masterpieces, but they glow with rich musical colours which spring from the composer’s understanding of their literary genesis. Thus Dass sie hier gewesen (Rückert) has a freedom, poetry and harmonic daring that would seem to defy chronology and belong to the world of Schumann’s Dichterliebe or even of Wagner’s operas and Wolf’s songs. The delightful Lachen und Weinen is the perfect foil for the serious and deeply moving Greisengesang, actually the first Rückert song of 1823 (we have already mentioned its performance during the summer of that year) and obviously an ideal vehicle for the ageing Vogl. Du bist die Ruh betrays its eastern inspiration by mention of the ‘Augenzelt’ (the tent of the beloved’s eyes) and by the tone of the music which suggests the measured incantation of an eastern prayer, whilst being one of the priceless pearls of western music. In contrast, Die Wallfahrt is an unknown fragment from the same period and poet. In November 1823 Schubert, in an optimistic frame of mind, writes to Schober (away in Breslau) that his health ‘seems to be firmly restored at last’, although various symptoms of the sickness continued to plague him on and off for quite some time. The old circle of friends was now breaking up: Schober was on his acting sabbatical, Kupelwieser was in Rome, Bruchmann had turned religious and was not nearly as much fun as before. A rougher, coarser type of young man had invaded the reading circle, and the composer was less and less inspired by the company he found there. ‘Riding, fencing, horses and hounds’ were the topics of conversation; ‘I don’t suppose I shall stand it for long’ Schubert wrote. The very affectionate tone of the letter to the absent Schober (‘Please still my longing for you by some extent at least by letting me know how you live and what you do’) ends with a curious phrase: ‘Only you, dear Schober, I shall never forget, for what you meant to me no one else can mean, alas!’. That ‘alas’ (leider) is haunting mainly because it is puzzling. Why does Schubert doubt his ability to find such friendship again? Do the present circumstances of his life play a part in what appears to be a renunciation, and do they refer to something more permanent than Schober’s absence from Vienna? After all, Schubert’s infection meant that, for fear of infecting a partner, he could not hope for sexual intimacy in the forseeable future. The passage in this letter has usually been taken to imply that Schober is simply an irreplaceable friend; and this may well be so. But another reading of that ‘no one else, alas’ is that Schubert is now forced to renounce any physical aspect in his close friendships, and thus can never again expect to experience sexual intimacy – with anyone. If the composer’s illness is indeed behind this rueful acknowledgement, it would throw new light on the past history of his long friendship with Schober (one of the most complicated and difficult to fathom of all Schubert’s relationships) and provide further pabulum for the continuing debate on sexuality in the composer’s circle. The year 1824 begins with the sound of breaking glass. In the company of Dr Bernhard, Schubert announced his presence at the home of Ludwig Mohn by throwing a stone at the window pane and shattering it. It was to be a year which still resounded from the shock-waves of the previous thirteen months. Having fared so badly with the music for the theatre in 1823, it seems that Schubert now decided to make himself well-known through instrumental music. In a letter to the painter Leopold Kupelwieser in Rome (31 March 1824), Schubert had already written of this new ambition to find fame through a means other than vocal music. This extraordinary document looks back to the past trials of 1823, and also to the future, however uncertain that might be. It begins with one of the most powerful Jeremiads ever penned by a composer, and is rendered more powerful by the fact that he chooses to quote one of his song texts – Goethe’s Gretchen am Spinnrade – in much the same way as he was to use other songs as starting points for several instrumental works during 1824: I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who, in sheer despair over this ever makes things worse and worse, instead of better; imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have perished, to whom the felicity of love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain … ‘My peace is gone, my heart is sore, I shall find it never and nevermore!’ I may well sing every day now, for each night, on retiring to bed, I hope I may not wake again, and each morning but recalls yesterday’s griefs. Schubert then goes on to bemoan the break-up of the reading circle and the sad lack of his friends who all seem to have abandoned Vienna, for various reasons, at the same time. Within a few lines, however, the tone of the letter changes; this document is one of the most powerful illustrations of what might be called the Lachen und Weinen aspect of the composer’s personality: tears are often to be discerned in Schubert’s smiles, but here, quite unexpectedly, we find smiles amidst the tears. His new publisher Leidesdorf is praised. He tells Kupelwieser, not without a note of pride, of two quartets recently composed (two of the greatest – the A minor and Death and the Maiden) as well as the magical Octet. In the first quartet he incorporates a musical echo of the Schiller setting Die Götter Griechenlands, a song of longing for former happy times, and in the second, the famous Der Tod und das Mädchen. The A minor Quartet had been given a successful performance at the Musikverein. Another work of 1824 is the set of variations for flute and piano based on Trockne Blumen, the eighteenth song from Die schöne Müllerin. Schubert, it seems, is still musically ambitious, however depressed. He admits to Kupelwieser that he is using these chamber works as stepping-stones towards writing a grand symphony. And, in stark contrast to the sentiments at the beginning of the letter, he tells his friend that he intends to give a concert of his works to rival the sort of thing that Beethoven is doing. So it seems that Schubert associates song-writing (and should we be surprised?) with a golden age which he now regards as having come to an end as far as he is concerned. For a period, song is reduced to reminiscence and rueful quotation. This accounts for the fact that the composing of new lieder plays such a tiny part in 1824. The composer must also have been depressed that so little stir was caused by the publication, in three parts, of Die schöne Müllerin in February, March and August; unaccountably, it was only after Schubert’s death that the beauties of this work seem to have impressed the public. If 1824 was the least fruitful song year of all, Schubert threw himself (in the earlier months at least) into chamber music. In March there is a letter from Moritz von Schwind to Schober which comments on the composer’s ceaseless activity, and that he scarcely had time to say ‘Good morning’ without looking up from his work. This was probably during one of the periods of strict medical supervision where he maintained a healthy diet and abstinence from alcohol. But there is no doubt that there is a drop in quantity of output, even if the quality of the 1824 music remains on the highest level. There are only four solo songs in 1824, and they were written as the result of Johann Mayrhofer’s private publication of his Gedichte. This slim volume does not contain the composer’s name on its list of subscribers (the reason why has been the subject of much speculation) but it seems to have re-focused the composer’s affinity with Mayrhofer’s genius. In bidding farewell to the work of someone who had been his intellectual mentor more than any other, Schubert gifts us with a number of new masterpieces. Despite the fact that it seems that poet and composer had fallen out (their friendship had begun in 1814, and reached its apogee between 1818 and 1820 when they had lived together for nearly two-and-a-half years) Schubert could not resist the powerful pull of Mayrhofer’s verse. One poem enchanted him so much that he set it twice, first as a solo song (Gondelfahrer) and then as a work for four male voices. The sense of a crisis surmounted (‘the ancient curse is no more’) in Der Sieg perhaps reflects the optimistic side of Schubert’s nature after his illness; even Abendstern, the isolated star of love shunned by its brothers, is clothed in heart-stopping music which mirrors the tender resignation of someone who has come to terms with the fact that he can ‘sow no seed … see no shoot’. The grandeur of Auflösung is reminiscent of the closing lines of Schubert’s poem Mein Gebet. As he lay submerged in the mercury baths of the Allgemeines Krankenhaus the composer hoped for nothing less than rebirth and transfiguration. If the song is partly to do with death, it has an ecstatic energy which suggests a new beginning, mortal flesh reinvigorated by an experience both horrific and divine. There is certainly nothing else like this song in the composer’s output. Like Saint-Saëns’s Tournoiement – Songe d’Opium it suggests what would now be termed an ‘out-of-body experience’; this song of the soul is the sole song which suggests that Schubert might have known what it was to go on ‘trips’ of an extraordinary nature, courtesy of the opium sessions at the Wasserburg café. In a life not rich in travel there was one big trip in 1824. For almost five months in the middle of the year, from May to October, Schubert allowed himself to be lured, once again, to the Hungarian estates of Count Esterhazy at Zelisz where he was nominally music-master to the Esterhazy countesses, Marie and Karoline. It is true that he enjoyed a more elevated position, in social terms, than he had been accorded in 1818. Apart from much beautiful dance music, the composer lavished his attentions on the form that he made his own in a similar way to the lied – the piano duet. Thus the four-movement ‘Grand Duo’, the mightiest of his works in this genre, was written in June 1824. The Eight Variations on an original theme D813 dates from the same time, as does the Divertissement à l’hongroise D818. Apart from the dance pieces which were obviously composed for gatherings and parties, and the duets which were almost certainly created for opportunities for the composer and Karoline to work closely together for eminently respectable musical reasons, there was one substantial vocal work. This was the quartet Gebet, a work proposed at breakfast and ready the same evening – the work of one day – with words by de la Motte Fouqué. Here we experience that side of Schubert which was able to submit for short periods to the conditions – writing music to order – which Haydn knew for most of his creative life. This second Hungarian episode in Schubert’s life is richer in biographical speculation than in music, mainly because of the young Countess Karoline Esterhazy who has long been named as the composer’s beloved. In a letter to Schwind in that summer, Schubert referred enigmatically to someone as a certain ‘star’ in his life – and that someone, shiningly beautiful and remote, was almost certainly Karoline. That these two never had an affair with each other is certain; in any case, for the reasons outlined above, Schubert, unless he was reckless and unconcerned about the safety of others, was in no position to have an affair with anyone. That he was extremely fond of the countess, and had a major crush on her is, however, almost beyond doubt, despite the typically Viennese obfuscatory discretion of the documents. After Schubert’s death, the story of this romance became commonplace in almost the same way that the Lilac Time fiction about the composer’s love-struck visits to the Drei-Mädel house was mercilessly embroidered for public consumption. The story of Schubert and Karoline has lately been down-played by the commentators, particularly those who would cast Schubert as gay. But it cannot be denied that everything points to the fact that this pretty, intelligent, and musically gifted woman was the focal point of the composer’s romantic idealism in the wake of his illness. The gruesome facts of Schubert’s syphilis, including, no doubt, memories of the whore (as it is traditionally thought) who had infected him, were now counterbalanced by the image of an unattainable Madonna. Even those who believe that there was a homosexual side of Schubert’s make-up should find no inconsistency in the well-documented reverence the composer felt for Karoline. It merely underlines that in one sense nineteenth-century society was freer than our own: before the invention of psychological terms to describe, and pin down, sexual preference, it was perhaps easier to feel that emotional options remained open for longer than in the label-obsessed sexual ghettos of our own age. Despite the presence of the ‘star’ – Karoline – Schubert found life at Zseliz trying and lonely. Schubert himself wrote as much to Schwind. Far from relishing the fact that he was alone with the object of his affections, he complained of feeling starved of intellectual company. A letter that the composer wrote to Schober once again quotes from a Goethe poem which he had already set (the nostalgic Erster Verlust) which longs in vain for the return of former happy times. Schubert was anxious to return to Vienna, and managed to do so ahead of schedule, in mid-September. This was thanks to the post-chaise of Baron von Schönstein who gave Schubert a lift back to the city and who amusingly described the composer’s clumsiness in breaking a window of the carriage, causing its occupants to freeze. The remainder of the year was not, however, creatively busy. The only work which was composed in the two-month period of November and December was the Sonata for arpeggione, and possibly the second of the Suleika songs (Volume 19) for Anna Milder-Hauptmann. The composer had moved back to the schoolhouse in the Rossau on his return from Zelisz and, whatever the state of his health, the year seems to have ended with the usual celebrations. The reason why the song Lied eines Kriegers bp was written on 31 December is not known. If Schubert was capable of writing the complicated Gebet in a single day, it would not be unreasonable to expect that this song was knocked up on the day for a New Year’s Eve party. It certainly suggests an occasion when a certain number of hearty masculine voices would find themselves assembled together. All in all, we know remarkably little about the period between October 1824, when Schubert returned from Hungary, and April 1825. As we have said, Schubert had gone back to live in the family home in Rossau, and he remained there until February 1825 when he took up lodgings near the Karlskirche in the suburb of Wieden, close to his young friend Moritz von Schwind. The inference must be that during that winter Schubert was once again unwell; certainly, he pulled in his creative horns, and it is possible that he returned to the general hospital. There are several pieces of circumstantial evidence that support this theory: for example, a letter from Schwind makes it clear that at the first of a weekly series of Schubertiads at the home of Josef Witticzek on 29 January, the composer himself was not present; also Kreissle von Hellborn refers to the ‘well-authenticated fact’ – the information came seemingly from several of the composer’s friends – that the settings of Karl Lappe, Der Einsame (and thus also probably the same poet’s Im Abendrot) were composed in the general hospital. These beautiful works are thought to date from early in 1825, so there is nothing concrete to gainsay Kreissle’s statement. Another song from the beginning of the year is Des Sängers Habe. Here it is Franz von Schlechta, a former schoolmate of the composer, who touches on the theme of survival in adversity that has already been elaborated by Schober in Pilgerweise. Once again one supposes that Schubert’s plight was the subject of much contemporary discussion and compassion that has not come down to us in documentary form, and that his tragic situation seemed to his friends to be so sad and poignant a plight as to be a subject for poetry. For this group of sympathetic friends, ‘singer’, ‘bard’ and ‘pilgrim’ seem all to have meant ‘Schubert’, and the amateur poets in the composer’s circle encouraged him to believe that his art would survive catastrophe. Just as he had earlier set Mayrhofer’s Geheimnis which refers to his own divine gifts, Schubert seems not to have demurred from giving these poems musical life. Indeed, the putting of these texts to music was living proof of the very triumph of art over adversity which the poets had praised. The Schober and Bruchmann poems come from earlier in the crisis, but the Schlechta work seems to acknowledge, in a powerful and personal way, that music had healing powers, that it really was as elevated and powerful a force as Schober had once claimed in his poem An die Musik. Sadly, Schober himself was in Breslau, attempting to be an actor, and Bruchmann had begun to embrace religion in a way that would make him renounce his former friendships in an almost violent manner. He was also the cause of a major rift in the circle when he prevailed on his sister Justina to break off her engagement to Schober. (What did he know about Schober, we wonder, to make him take this extreme course?) The composer predictably sided with Schober and there was no doubt that the mood of the circle had generally soured. Schubert’s letter from Zelisz when he quoted lines from Goethe’s Erster Verlust, complaining that things were not as they used to be, was more prophetic than he realised. The light and warmth of friendship seemed something of the past. There were always compensations. Schubert’s works were performed in Vienna more than ever before. The list of publications for the year make impressive reading; Schubert was now dealing with a number of publishing houses and had little reason to regret his 1823 break with Diabelli. Indeed, even that rift would be mended in time. Schubertiads were also more frequent and were now more glittering affairs than they used to be; we find them taking place in such houses as that of the singer Katherina von Lászny. This is a sign that even if the circle of intimate friendship was not what it was, admiring acquaintances now included the great and the good, as well as the not so good (Lászny was a courtesan as well as a patron of the arts). People were beginning to ask for pictures of Schubert, and the famous watercolour by Wilhelm August Rieder (1796-1880), reproduced on the cover of this booklet, was done in May 1825 and on sale in an engraving by J H Passini in time for Christmas of that year. A new generation of younger Schubertians had emerged who took the place of those who had slipped out of sight. Two nobly born young men now became a regular part of the composer’s life. The first of these was the painter Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871). Seven years younger than the composer, he was also the most talented of the Schubertians – something which seems proved by the distinction of his later career. The artist had known Schubert since 1821, but close friendship with Schubert was never instantaneous. As time went on, Schubert felt more and more attracted by the young Schwind’s energy, his love of life and his sense of fantasy; he even referred to him as his ‘beloved’ which has been written off as a typical exaggeration of an age given to hyperbole. Schubert, like most of us, liked and admired talented people; if he was a snob at all, it was in this regard, and young Moritz exactly fitted his idea of a comrade-in-art. (The more self-regarding Schober seems to have seen Schwind as his disciple.) The painter expressed his devotion to Schubert in no less romantic terms. He seems less attractive when displaying the arrogance of youth: Schwind was rude to those who bored him (like the singer Vogl), and he encouraged Schubert when in party mood to behave like a teenager rather than a great composer in his late twenties. (Johanna Lutz, fiancée of Kupelwieser, notes that both Schubert’s and Schwind’s behaviour seems childish in terms of their hatred for Bruchmann when he foiled Schober’s engagement to his sister Justina, something which led to a major feud between former friends in the circle.) In this year Schwind was particularly proud of a sequence of thirty drawings illustrating the imaginary wedding procession of Mozart’s Figaro. Schwind depicts himself, not without humour, as one of the heralds at the ceremony blowing his own trumpet. Much more of a newcomer to the circle was the poet and playwright Eduard von Bauernfeld (1802-1890). He was musical enough to have admired Schubert’s work long before becoming his close friend. Unlike most of the other Schubertians (excluding Schwind of course), Bauernfeld’s subsequent fame did not depend on his association with Schubert. By 1902 the Burgtheater had presented no less than 1100 performances of 43 Bauernfeld plays. We owe only one Schubert song to Bauernfeld (Der Vater mit dem Kind) but he was the translator of Schubert’s Shakespeare setting An Silvia and the librettist of his last opera Der Graf von Gleichen. At this point in Schubert’s life, the company and friendship of these two talented young men was of great importance to his morale. Further new friendships enhanced the spring of 1825. Schubert, ever in search of new poetic collaborators now that he had so thoroughly mined the poetic veins of Goethe and Mayrhofer, was in touch with the polyglot poet and translator Nikolaus Craigher de Jachelutta. With Craigher’s help Schubert hoped to publish his songs in various languages (English was a priority) by setting metrically compatible translations of original poetry. But another new contact was much more glamorous – the delightful actress and singer Sophie Müller (1803-1830). We note from a diary that she kept in the spring of 1825 that she was frequently visited by Vogl and Schubert, and that songs, both old and new, were performed by her and Vogl with the composer as their accompanist. Sophie read a great deal and was a Walter Scott enthusiast. (She also read Fennimore Cooper and it might have been from her that Schubert acquired a taste for the American author whose work was to accompany his dying days in 1828.) In any case this friendship (and we can detect the transference of some of the composer’s reverence for Karoline Esterhazy on to Sophie’s shoulders) seems to have inspired new lieder. From this period date Die junge Nonne (a Craigher creation which, it seems, Sophie was the first to sing); on the other hand Der blinde Knabe, Schulze’s Im Walde, and Totengräbers Heimwehe seem to have been designed for that mixture of drama and pathos which was Vogl’s speciality. The earlier Scott settings Lied der Anne Lyle and Gesang der Norna were perhaps written to please Sophie, and one cannot help wondering whether the whole Lady of the Lake cycle was somehow conceived as something that Sophie Müller and Johann Michael Vogl could perform together. We know that the three Ellens Gesänge were begun in April 1825 (and finished on holiday that July) and that Lied des gefangenen Jägers and Normanns Gesang were conceived at the same time. The exact date of the composition of the two remaining items which complete this opus (Bootgesang bq and Coronach) are not known. It is likely that they were left to the summer, as Schubert rounded out the opus (in quasi-operatic fashion) to include a chorus. Song enthusiasts are apt to forget that somehow the composer had time for other creative work: the A minor Piano Sonata, D845 (which, significantly, shares some of its musical material with Totengräbers Heimwehe) and the unfinished Sonata in C major, the so-called Reliquie. In early June 1825 Schubert’s Opus 19 was published – three songs by Goethe: An Schwager Kronos, An Mignon and Ganymed. He wrote a short letter to Goethe to be enclosed in a special presentation copy, making one last attempt (as futile as the rest) to get in touch with the poet whose approbation he had so long desired. Leaving those concerns behind him in Vienna, Schubert now embarked on a journey during which he literally had the time of his life. Just as the Zelisz summer of 1818 had been followed by the Upper Austrian sojourn of 1819, the second, and last, Zelisz summer of 1824 was now followed by a glorious holiday in Upper Austria which lasted some nineteen weeks. The itinerary seems to have been invented, as in all relaxed holidays, as it went along; each of the main centres was a springboard for shorter excursions. The first of a number of Linz sojourns that summer was followed by visits to the two monasteries of St Florian and Kremsmünster. Here the composer shone as an accompanist, piano-duettist and soloist. His duo work with Vogl (‘as though we were one at such a moment’ as Schubert puts it) was rapturously received, and his solo piano playing was commended for the fact that ‘the keys became singing voices’ under his hands, a style different from what the composer called the ‘accursed chopping’ of certain fashionable virtuoso pianists. Back in Steyr Schubert enjoyed the company of two families whom he had known since his first holiday in Steyr in 1819 – the Schellmanns and the Kollers. He was also once again in touch with Sylvester Paumgartner, Steyr’s great patron of the arts, who had played such a crucial part in the commissioning of the ‘Trout’ Quintet in 1819. On the Gmunden leg of the holiday Schubert stayed with the merchant Ferdinand Traweger who had a roomy house overlooking the lake. Here the composer struck up a friendship with the youngest son of the house, the four-year-old Eduard, who for the rest of his long life remembered Schubert teaching him to sing Morgengruss from Die Schöne Müllerin. The Traweger family (by arrangement with Vogl who paid the rent) gave Schubert an informal and comfortable base for much music-making in the area. This included informal concerts at various places: at the home of Johann Nepomuk Wolf and his daughter Anna; at the residence of Franz Ferdinand Ritter von Schiller who was the local grandee (‘monarch of the whole Salzkammergut’ as Schubert himself put it); at Schloss Ebenzweier, three miles away from Gmunden on Lake Traun, the home of the beautiful and sympathetic Therese Clodi. At Steyregg, on the way back to Linz, Schubert and Vogl made a deep impression on the Count and Countess Weissenwolff who were particularly taken with the Lady of the Lake songs. During this holiday it was Vogl’s performance of the ‘Ave Maria’ (Ellens dritter Gesang) which seemed to have moved people most. These episodes of musical socialising were counterpointed by a longer stay in Linz with the Ottenwalts where only the uncertainties of the weather (either rainy, or exceedingly hot) caused any problems. Anton von Ottenwalt rejoiced in the chance to get to know the composer better. Vogl and Schubert then moved on to Steyr for two weeks, and thence to Salzburg, stopping at Kremsmünster again on the way. As the duo progressed to Salzburg, the natural sights were increasingly spectacular. Schubert had never seen such dramatic and imposing scenery (‘the country surpasses the wildest imagination’ he wrote to Bauernfeld), and he had never encountered such a variety of architectural riches. The composer’s brother Ferdinand had particularly asked Franz to record his impressions of all this, which the composer duly did in prose that is both carefully detailed and colourful. Instead of posting these letters, Schubert handed them back to Ferdinand on his return to Vienna; excerpts were eventually published in Ferdinand’s geographical treatise, Die kleine Geographie. Schubert and Vogl found Salzburg rather run-down; it was certainly a less interesting cultural centre than it had been in the time of Mozart. They were received at the home of Count Platz where their music-making probably brought them a fee. The two men took a lot of exercise, climbing both the Mönschberg and the Nonnberg, which rewarded them with wonderful views over the town and valley. They also visited various churches, and Schubert, delighted with the light and airy rococo style (‘this extraordinary brightness has a divine effect’) paid his respects to a monument honouring Michael Haydn, a composer whose church music he had known since boyhood. This episode, the most physically active time of the holiday, was followed by the short journey to Gastein where Vogl was anxious to begin to take the waters. The recommended length of the cure for gout was three weeks, and that is exactly how long they stayed. It was in this tranquil spot that Schubert had time to compose. The beauties of the Piano Sonata in D major, D850, are testimony to the inspiring surroundings, and John Reed’s thesis that the lost ‘Gastein’ Symphony is none other than the ‘Great’ C major Symphony composed, at least in part, during this period, is now generally accepted. Thus, happier than he had been for a very long time, Schubert achieved his ambition to write a grand symphony – the very work that Schubert told Kupelwieser he was working towards in his sad letter to the painter in Rome in 1824. In Gastein there was, amazingly, also time for song composition. This was due to the presence there of Ladislaus Pyrker, the poet whom the composer had first met in 1820 chez Matthäus von Collin. In that year Pyrker had been appointed Patriarch of Venice (then under Austrian control) and it seems that Schubert was much taken by the strength and personality of this important cleric with his imposing poetic style. The songs of Op 4 had been dedicated to Pyrker, and now, perhaps encouraged by the poet himself (and guided in terms of text selection), Schubert set about two substantial Pyrker settings. These are Das Heimweh and Die Allmacht. The latter song in C major has much of the ‘Great’ C major Symphony about it. Another important, and highly spiritual, song was almost certainly composed at the same time: Fülle der Liebe with a text by Friedrich von Schlegel. With the end of the Gastein episode Schubert had imagined that he and Vogl would return to Salzburg for more leisurely sightseeing. But the singer was having none of it and insisted on a return to Gmunden via an overnight stop in Kremsmünster. Then, after only six days, he announced, to Schubert’s stupefaction, that they would be immediately returning to Steyr. The exciting part of the holiday was suddenly over. To be fair to Vogl, he had had a great deal of Schubert’s company, and paid all the bills; he was anxious to journey on to Italy before the autumn had progressed too far, and he needed to get ready to do this from his home base in Steyr, Although there was a further fortnight in that town, Schubert now realised that he would have to return to Vienna about a month earlier than planned. He made use of his remaining time by returning to song-composition. From September 1825 comes a further setting of Friedrich von Schlegel (the charming Wiedersehn), Abendlied für die Entfernte6 with a text by the other Schlegel brother, August, and two songs from Schütz’s play Lacrimas – Lied der Delphine and Lied der Florio. The coda to the summer was another short stay at Steyregg with the Weissenwolfs (this time without Vogl) and a final musical evening at the home of Anton von Spaun in Linz. Schubert travelled back to Vienna in the company of the pianist Josef Gahy. Returning to Vienna had its compensations as well as its temptations. Schubert found two old friends whom he had much missed: Franz von Schober, now returned from his fruitless attempts to establish himself as an actor in Breslau, and Leopold Kupelwieser who had come back from Italy. Schober had long been admired by Schwind, almost to excess, and now Bauernfeld met him at last. His reactions were more guarded: he found Schober ‘interesting’, but also immediately perceived his weaknesses. Indeed, the letters of Bauernfeld add a new and very perceptive note to the Schubert documents. He was an ironic satirist by nature, and seems to have been able to distance himself from the heady enthusiasms of a group of aspiring students. This enabled him to take a rather more realistic, and sometimes comic, view of people. It is no surprise that he later became well-known as a writer of comedy. His New Years’ Eve pantomine Der Verwiesenen – ‘The Outcasts’ – (where all the members of the circle are assigned a part) tells us a great deal, and with devastating honesty, about the different characters of the Schubert circle. During the summer, Bauernfeld had written a letter to Schubert in Upper Austria proposing that he, Schwind, and his ‘fattest of friends’ (Schubert of course) should share an apartment, an idea that did not appeal to the composer quite happy with his arrangement at the Fruhwirthaus. Kupelwieser, on the other hand, distanced himself from the circle. He was a man of strong religious convictions, happy to spend most of his time in the company of his fiancée Johanna Lutz, and he had little time for Schober. The latter now found himself surrounded by a new generation of young men who were not yet weighed down by the responsibilities of maturity and were intent on having a good time. The autumn of 1825 seems to have been taken up with parties and a social life energised by Schober’s presence. After the announcement ‘Schubert is back’, Bauernfeld penned a short poem in his diary: Wirtshaus, wir schämen uns Hat uns ergötzt; Faulheit wir grämen uns Hat uns geletzt Taverns, we blushingly relate, Are where you’re sure to find us, For idleness, we grieve to state, Has lately undermined us. Bauernfeld continues: ‘Schober is the worst in this. True he has nothing to do, and actually does nothing, for which he is often reproached by Moritz’. After a holiday of fresh air and exercise, during which Vogl would have encouraged, if not enforced, moderation in drinking and eating, Schubert seems to have returned to his old ways of 1821/22. He was feeling much better, obviously, and may have told himself that he was cured. The earnest conversations of the summer with Anton and Marie Ottenwalt in Linz seem to have been forgotten: when the couple visited Vienna in the autumn Marie was much put out by the fact that Schubert failed to call on her. Much was forgiven him because of his genius, but Anton commented on the composer’s ‘burning [or demanding] sensuality’ (‘die Affektionen einer lebhaft begehrenden Sinnlichkeit’). One sentence from the perceptive Ottenwalt (who obviously knows the whole story of the composer’s illness through Josef von Spaun) shows this mixture of concern and affection: ‘Er ist heiter – und so hoff’ ich, auch gesund’ (‘He is cheerful – and I hope also healthy’). Schubert’s good intentions to remain celibate, knowing his condition and its possible dangers to sexual partners, may well have weakened. Like Schumann in a similar situation some years later, the doctors may have told him that the danger to others had passed. With Schober as the presiding master of ceremonies we see Schubert abandoning the strict regimes (not to mention the boring company of medical gurus) which had characterised the agonisingly sad period after his stay in hospital of 1823. The jollifications of this period are well typified by the choral quartet Der Tanz although its date is contentious. Certainly the work-catalogue for this period reveals little further compositional activity until December 1825 when the composer returned to the poetry of Ernst Schulze. He had set Im Walde earlier in the year, and almost certainly Auf der Bruck as well. Three further songs were written to continue (though not complete) whatever vague notion of a Schulze cycle might have been in Schubert’s mind: An mein Herz, Der liebliche Stern and Um Mitternacht. The year 1824 had yielded only four songs, but 1825 had been much more fruitful. Apart from partsongs, some twenty-five had been written, and almost all of them masterpieces. Graham Johnson © 2000