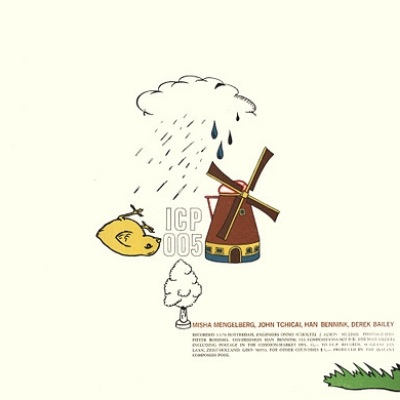

Misha Mengelberg, John Tchicai, Han Bennink, Derek Bailey

by Eugene Chadbourne The work of this quite interesting quartet, in which innovators from several different factions of modern jazz come together and stumble over each other, deserves to be revisited, particularly by listeners curious about how music got as weird as it did in the 20th century. Half the quartet are Dutch, the regular team of pianist Misha Mengelberg and drummer Han Bennink, by the time of this recording veterans of backing up everything from Ben Webster to this mess. Saxophonist John Tchicai is part of what is known as the Ascension team, meaning he was one of the chosen few called forward by John Coltrane in that style of ecstatic, multi-horn screaming jazz. Derek Bailey has his own musical world, a fascinating place to travel in especially when the stops along the way include the demented electric guitar style he utilizes here. That's four great players, but listeners will only accept what they do as fitting together if not horrified by the notion of several different things happening at once. That represents a contrast, not only to most known music but to some of the music these players make themselves. The recording simply entitled Instant Composer's Pool featuring a somewhat larger ensemble comes from the same time period but is a style of improvisation in which the players practically roll on top of each other in terms of compatibility, completing each other's thoughts and putting together complex spontaneous structures as if a team of carpenters raising the side of a barn. Different sorts of things happen on this record, in which the program consists of a series of so-called "fragments," or edited sections from the gigs. At one point Mengelberg is into a full-blown modal jazz piano solo, springing out of something the saxophonist has played. Bennink is accomodating, but meanwhile Bailey is creating sounds that bring to mind someone removing needles from their leg. The guitarist and saxophonist really do play differently, and what happens often is that the latter lays out when the former is in the height of his glory. What makes the quartet work is that no matter what one of the people does, at least one of the others can come up with something complementary and fitting. Since the group isn't trying to have a normal combo sound of one kind or another, that leaves the other two free either to hang fire or to do something else, sometimes equally fitting, sometimes ridiculous. The editing, which can be a problem with records of free improvisation, may in this case cover up whatever flabby moments this group might have also had in its sets -- but that hardly hampers the pleasure of this delightful album.