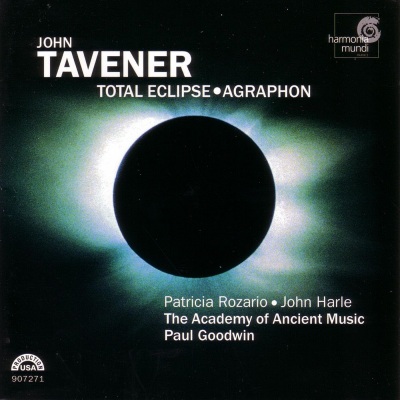

Tavener: Total Eclipse & Agraphon

by Thom Jurek Harmonia Mundi continues the series of world premiers by John Tavener. It began with the worldwide smash hit Eternity's Sunrise. Using the same group and conductor, Tavener offers two more world firsts in his mammoth symphonic piece, Total Eclipse, written for orchestra, soprano saxophone, countertenor, tenor, choir, and a percussion ensemble that includes 19 tympani and Tibetan percussion instruments, including the ritual temple bowl and tamtam. Agraphon, from 1995, is an orchestral setting for Patricia Rozario to sing the Greek mystical poetry of Angelos Sikelianos. If all of this sounds exotic, it is, and should come as no surprise to anyone who has encountered Tavener's large-scale works in the past. Extreme dynamics, multiple intervals, the piling on of dominant sevenths and sixths, wide spaces inside the score where non-predetermined expressions required by either conductor or soloist are essential to the narrative of the work, and so on. Tavener is also insistent on the use of performance space in such a way that soloists move around in it, and orchestra and singers are not visible to one another -- and yes, all of this does come across on a recording. Total Eclipse is an illustration of "Metanoia," or "change of mind," in regards to the conversion of St. Paul. The orchestra begins with the rumble, menacing though it is of the tympani, signifying the tumbling rocks and earthquakes that occurred at the death of Christ. John Harle's soprano, bleating and screeching through the orchestra, represents the voice of Saul, cursing in hatred at Jesus and those who accepted him as the Messiah. The voice of Christ, the one that calls to Saul both from the cross and from the Eternal, is signified by the tenor (a boy of 19), a baroque oboe, the temple bowl, and tamtam: There is sweetness and love yet authority in the voice. Harle's soprano does an excellent job of not knowing how to respond to this call, though it grows softer and closer. When finally, the blinding occurs the choirs chants the word "Metanoia" over and over until the text takes over, and the third and last part begins, where the divine love of Christ begins to speak thorough Paul until his death as a martyr. Does it work? For these period instruments and the voices, Tavener has created an architecture unlike any in music in the early '00s, and he stands with feet firmly planted in both camps: the avant-garde and in the historical lineage of composers from Palestrina to the present who have conceived large works on sacred themes. The Academy of Ancient Music plays with great restraint and emotional intensity, and Paul Goodwin conducts with a relaxed but complete control. Harle, who is one of the most diverse saxophonists to date, becomes Saul/Paul with so much emotion it is almost overwhelming. This is an "ikon in sound" standing at the gateway where musical language and Divine intertwine and whisper lovingly to one another. The second work here, Agraphon, features Rozario -- one of the finest sopranos yet -- illustrates the poetic text's juxtaposition of every perceivable thing both natural and humanly created being an extension of the invisible/supernatural/divine realm. They are mirrors of one another. Tavener uses two ideas in illustrating the text of Sikelianos: The first segment of this 22-minute work is comprised of an opening series of intervals that appear to be endless in their symbolic representations. This is the music of the spheres, the voice of the angels who occupy a small but inconceivably difficult space between the flesh and the spirit. The second idea is best expressed by the composer himself: "...Then there is the apparent evil of the endless series of spiraling sixths and sevenths falling without apparent hope of redemption through an eternal geometric series, down into a hellish realm....The music ends fiercely at the incomprehensible clash between the Divine and the human." For the listener, the series of Eastern melodies that opens the piece, articulated gorgeously by Rozario, becomes ever more nightmarish and intense, threatening both lyric and musical architecture ability to remain whole -- often failing and splintering into chaotic yet purposeful noise. The work is haunting and dramatic, never faltering despite the weight it carries and is, if not resolved in the end, at least left resonating, echoing a series of musical and spiritual questions in the heart of the listener. Music can do no more than this. The sound is phenomenal despite the cavernous conditions these works were recorded in. Tavener has hit his stride over the past seven years, and continues to dazzle with both the depth and dimension of his vision and his increasing ability to realize it in its musical totality.