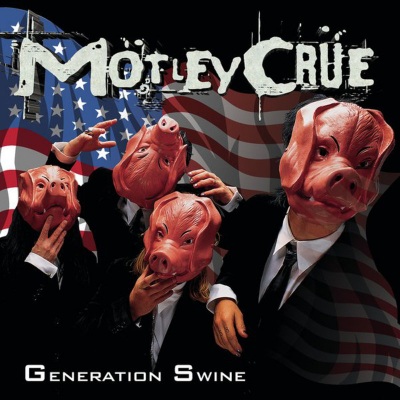

Generation Swine

by Stephen Thomas ErlewineNo other band embodies the successes and failures of '80s metal better than Mötley Crüe. After Dr. Feelgood made them one of America's biggest rock bands, the group won a record-breaking, multi-million dollar contract from Elektra in 1991. Within months of signing, Nirvana banished hair metal from the charts, and, shortly afterward, singer Vince Neil left the band. They struggled through a virtually ignored album in 1994 before reuniting with Neil in 1996. According to rumor, they were pressured by the label to reunite, which makes sense: their investment was completely blown, and their only chance to make any money at all was to have the original band come back together and market that as an event. Of course, it benefited the band as well, since by the time they released Generation Swine in the summer of 1997, it was nearly a full decade since Dr. Feelgood -- there was no other way they could get any attention. Not that the Crüe doesn't try to shake things up, hiring Nine Inch Nails keyboardist Charlie Clouser to bring some alternative and industrial textures to Generation Swine. It doesn't work at all, because Mötley Crüe is tied down to their sleaze metal, which wouldn't be a bad thing if they had come up with any catchy riffs. Instead, they're simply recycling old ideas and sounds. And while Neil does sound better than John Corabi, the man who briefly replaced him, it sounds like the band made the tracks for any singer at all, as if his presence was just a coincidence. (At least that problem doesn't plague "Brandon," where drummer Tommy Lee sings a shockingly mawkish tribute to his first son.) Consequently, Generation Swine is nothing short of an embarrassment.