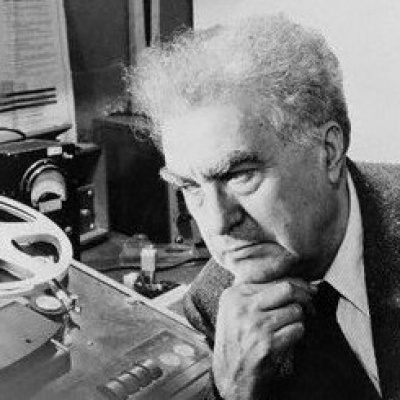

Edgard Varèse

by Jason Ankeny Criminally unknown throughout his own lifetime, composer Edgard Varèse was among the century's true creative visionaries; imagining music as bodies of sound in space -- its impact most profound as a physical experience -- his work sought to strip away convention and tradition, its massive, cacophonic power anticipating much of the experimental music to follow in its wake. Born in Paris on December 22, 1883, Varèse announced his intentions to become a composer while in his early teens, later studying under d'Indy, Roussel, and Widor; he was also encouraged in his pursuits by Claude Debussy and Romain Rolland. After a falling-out with his father, in 1907 Varèse relocated to Berlin, where he was befriended by Richard Strauss and Erik Satie; there he began to theorize that music should imitate scientific principles. He also became increasingly fascinated by the possibilites offered by electronic instrumentation. Varèse returned to Paris in 1913; his earliest compositions were left behind in Berlin, where they were soon lost in a fire. After pursuing a career as a conductor, he settled in the United States in 1915, forming the New Symphony Orchestra and attempting to drum up interest in his proposals for new electronic instruments. His first subsequent composition, Amériques, was not completed until 1921; that same year Varèse founded the International Composers' Guild, a group dedicated to performing new compositions of both American and European origin. He wrote much of the material himself, including a series of pieces for orchestral instruments and voices which featured 1922's Offrandes, 1923's Hyperprism, 1924's Octandre and 1925's Intégrales. The ICG also premiered key works by Alban Berg, Charles Ives, Henry Cowell and Anton Webern. In 1928, Varèse travelled back to Paris to rework part of Amériques to accommodate the recently-constructed ondes martenot, a theremin-like instrument which produced sound via a moveable electrode. Two years later, he composed Ionisation -- his most renowned non-electronic work, it featured only percussion, and was created as a means of exploring and manufacturing new sounds. Rejected by both the Guggenheim Foundation and Bell Labratories in his attempts to recieve funding for an electronic music studio, Varèse next turned to 1934's Ecuatorial, composed in part for theremin; later that year he returned to the U.S. only to discover that another of his grant requests had been denied. The setback proved crippling -- while waiting for modern technology to catch up to the music he heard in his head, Varèse spent over a decade suffering from depression, his creativity stifled. Aside from the 1936 flute piece Density 21.5, Varèse was largely silent until 1951, at which time an anonymous donor bought him an Ampex tape recorder. The gift allowed him to finally begin to realize the music he'd begun striving towards decades earlier, and he began compiling the sound fragments which complemented his project Déserts, begun in acoustic form nearly 30 years prior. Varèse eventually travelled to Paris to work on the piece alongside musique concrète trailblazer Pierre Schaeffer, and upon its completion in 1955, Déserts became the first piece transmitted in stereo over French radio airwaves. Varèse then went back to New York, where he remained until two years later, when he was invited to compose material for the 1958 World's Fair in Brussels; the end result was Poeme Electronique, his most admired and famous work. Produced in collaboration with the architect Le Corbusier, Poeme Electronique was a completely electronic work designed for broadcast over the 400 speakers scattered throughout the fair's Philips Pavillion; its impact finally began winning Varèse the recognition long due him, and his work began to be recorded and issued commercially. In 1962, he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the Royal Swedish Academy, and even received the Brandeis University Creative Arts Award. A year later, he received the first Koussevitsky International Recording Award. Apart from 1961's Nocturnal, Varèse spent the majority of his final years revising his earlier work, many of his earliest ideas now possible given the technological advances of the time. His final project, Nuit, was unfinished at the time of his death in New York City on November 6, 1965.